#NeuroThursday is back this week to talk about the #neuroscience of #synesthesia. What does it mean for a letter to have an intrinsic color, for a number to have a distance? And why the heck would this trait evolve in humankind?

Synesthesia is when "stimulation of one sense automatically provokes a secondary perception in another." The secondary perception can be direct ("9's are red") or associative ("9's make me think of red"), either counts.

Synesthesia comes in countless forms, but color-based are the most frequent. The most well-known is "grapheme-color" synesthesia, where a grapheme (written shape, e.g. letter or numeral) has a color - like the opening picture.

However, according to a big study in 2006, it turns out the most common is actually a "colored day" synesthesia. MONDAYS ARE BLUE, THE STRUGGLE IS REAL

Waiiiit, hold on. Metaphors don't count as synesthesia. The "blue" in "Mondays are blue" is an emotion, not a color. (Same goes for "seeing red" when angry.)

Hard to know whether the supposed frequency of "color-day" synesthesia is from people getting confused on that point, despite instructions. Regardless, the most common forms are definitely "something-color."

However, synesthesia doesn't require some kind of exotic experience. Current estimates for its frequency run over 4%, and it mainly occurs in individuals who are otherwise neurotypical.

(Interestingly, old studies said synesthesia was more common in women, but this is no longer believed to be true. Rather, women had been more likely to self-report their synesthesia experience.)

Even that 4% number is misleading. Synesthesia isn't some exotic brain malformation, it's the upper end of a universal spectrum of experience.

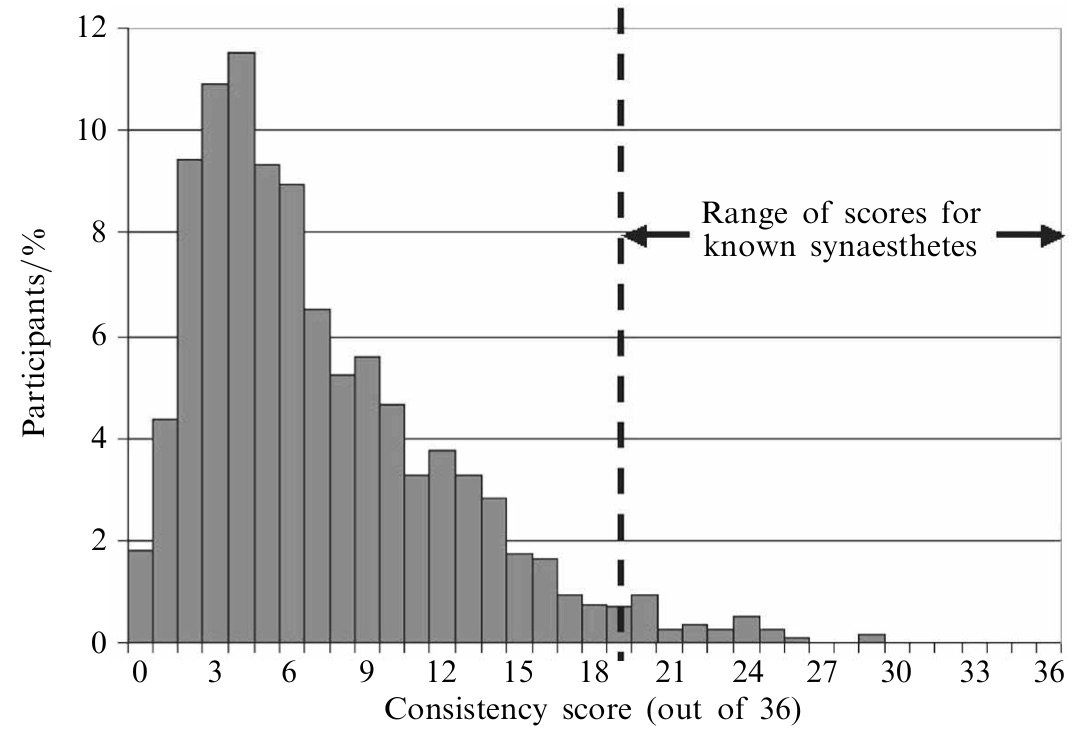

One way to measure synesthesia is by forcing people to classify letters to colors – and then do it again, and look for consistency across time. For synesthetes, these perceptions are real & consistent.

It turns out there aren't two groups, synesthetes and non. Rather, there's one group, and the ones we call "synesthetes" are just at the upper end of normal variability.

So now that we know what synesthesia is, try to figure out some neuroscience. Time to dive into tasty, tasty brains!

Synesthesia definitely arises during development (e.g. across childhood), and has a genetic component. We've known for more than a century that it runs in families.

One hypothesis is that it comes from extra-strong connections between the brain's sensory areas. Another is that synesthesia arises as "spillover" due to extra-weak inhibition from higher-level control areas.

In other words: is one lake flowing into another because the river is strong, or because the dam is low?

Recently, a group out of University of Wisconsin-Madison tracked down 3 families with sound-color synesthesia (rates ≥50% across 3+ generations) for a big ol' genetic study.

They found that these synesthetic families all had some rare variants of genes involved in axogenesis: the forming (-genesis) of long-range connections (axons) across the brain.

So these data (and others) support the idea that synesthesia comes from stronger-than-typical connections between brain areas. The river is strong!

Huzzah, a neuroscience story about synesthesia! But let's keep poking at this, because it can illuminate something bigger about genetics in the brain.

This study found 37 genes of interest, 6 associated with the formation of neural connections in early-childhood. But any gene has many variants. (Metaphor: if "sandwich-making ability" is a gene, there are many possible sandwiches to make.)

And across all those genes of interest, no variants were shared across families. Though each family had a similar form of synesthesia, they all got there by different routes.

Like any trait with a smooth curve of variability - like we saw in this plot - it's the result of many different genes interacting.

And that, at last, brings us back to "why would this evolve?" The answer is: it didn't have to. Not on its own.

There's surely some kind of evolutionary pressure on our genes for neural connections. But it looks like synesthesia occurs when those genes come out strong on the pro-connection side.

Imagine you have 6 coins to flip, and you want exactly 3 heads. Coin-evolution will keep each coin approximately fair, since that's the best way to achieve 3/6 heads.

But if you flip 6 fair coins, sometimes you end up with 6/6 heads. And in the long run, that's totally fine, since you'll still pass on six fair coins to your coin-children.

Importantly, "want exactly 3 heads" is a simplification. Maybe you just want *most* people to come up 3/6 heads. Maybe it's an advantage to have a population with a few folks who have 6/6 heads.

(A simplification with moral dimensions, too. People with 6 heads are not some kind of evolutionary error. For many reasons, simplest being that evolutionary history doesn't cause moral value.)

There's no way to know for sure what we "want." In fact, there's definitely no one answer. Evolution is about adapting to the environment - and environments change, across place and time.

Evolutionary psychology should be approached with extreme caution, because it's so easily misused to spin untestable stories about Why The World Must Be So.

But we CAN say that "synesthesia exists but is uncommon" does not prove either "synesthesia has advantages" or "synesthesia has disadvantages." It could be one, or both, or neither.

So here's a big-picture #NeuroThursday takeaway: synesthesia is a genetically-complex trait that puts the lie to evolutionary psychology. We know *how* it happens, but *why* is a question we cannot answer.

References: Prevalence of synesthesia via sro.sussex.ac.uk/14073/1/p5469.…, genetic study at pnas.org/content/early/…

Do let me know if that last part on evolutionary psychology was unclear - I could go into more detail another week, if there's desire! Though it's not really neuroscience.

If this #NeuroThursday crossed your streams in good ways or bad, share it around, or check out any of my other fiction & nonfiction! benjaminckinney.com/publications/

Orrrrr, sign up for my newsletter. 1 email/month (max) of updates, news, exclusive content, and the all-important cat photos. Never miss a #NeuroThursday or a story again! eepurl.com/bTeJIv

And lo, here is this week's #NeuroThursday discussion of #synesthesia and evolutionary psychology, condensed into webpage form! threadreaderapp.com/thread/1007413…

P.S: Here I am beating myself up the day after that I forgot to include this picture in the "people with 6 heads" tweet.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh