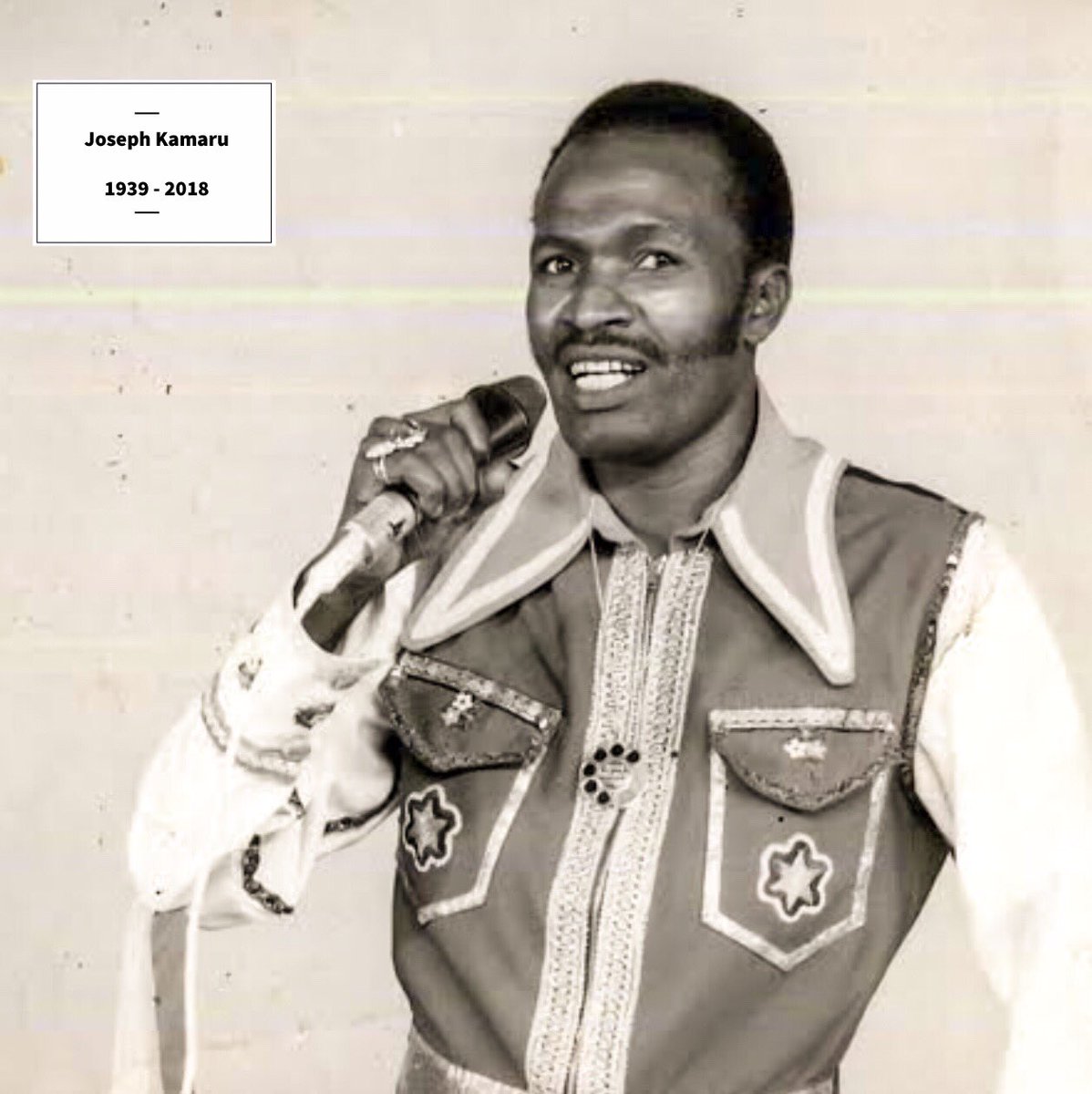

1/53 #HistoryKeThread: Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston’s Kilimanjaro Expedition

2/53 In the 19th century, there weren’t many British explorers and administrators who spent as much time wandering through the African continent as Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston did.

3/53 A Zoologist, Johnston not only spent three years administering part of Nigeria, but he was also the man who won over Nyasaland (Malawi) and Northern Rhodesia (Malawi) to eventual British crown rule.

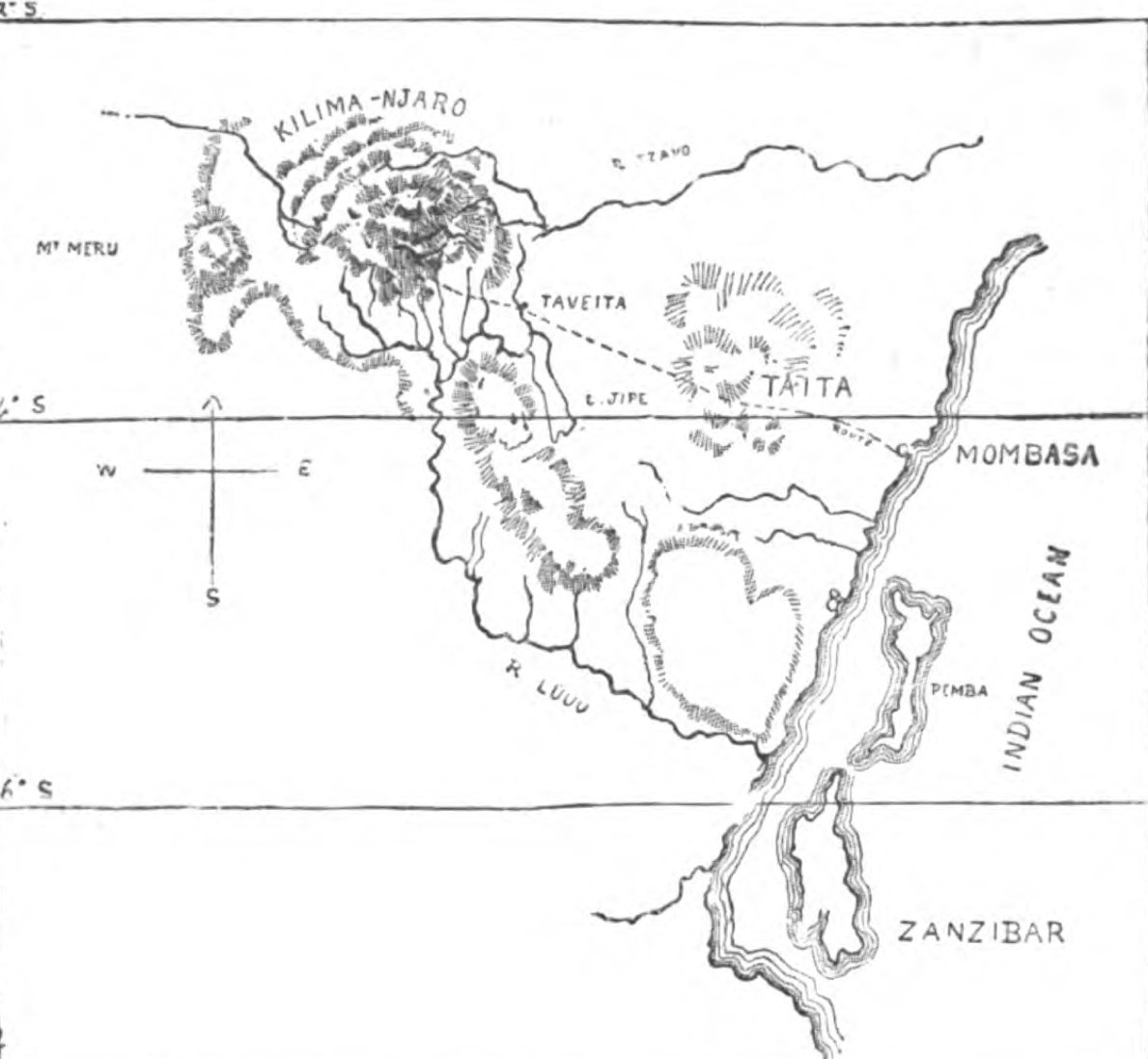

4/53 Moreover, Johnston’s input and networks were key in determining the Kenya-Tanzania border.

5/53 But, no, he is not the one who gave away Mt. Kilimanjaro to our Tanganyika brothers. In fact, contrary to a somewhat common but unfounded belief, Africa’s highest mountain has never been part of Kenya. Neither was the mountain hived off from Kenya.

6/53 Besides, we had no country borders in the old days. But that’s a story for another day.

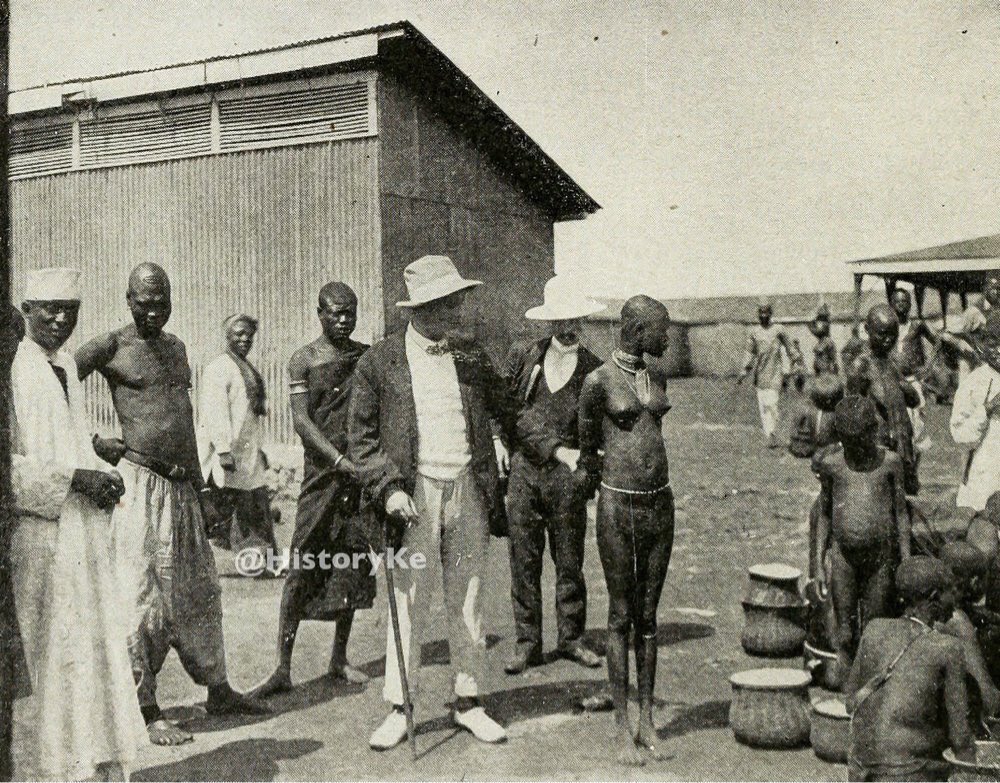

7/53 In 1894, Johnston set out to Kilimanjaro via Mombasa. He had spent some time in Zanzibar with Sir John Kirk, physician, explorer and former expedition colleague to Dr. Livingstone. As the British Consul in the spice islands, Kirk provided logistical and...

8/53 ...material support towards Johnston’s Kilimanjaro expedition.

9/53 Years earlier, experts in Europe had treated with disbelief German missionary Rebmann’s declaration - like Krapf’s earlier Mt. Kenya claim - of having discovered snow-capped Kilimanjaro. Africa was considered too hot for snow to exist, let alone survive.

10/53 And certainly not on a mountain close to the equator, geographers countered.

11/53 Poor Rebmann (pictured). Some skeptics even scathingly claimed he must have suffered fever in the African jungles and hallucinated.

12/53 But here was Sir Johnston. He carried the hopes of many geographers in the United Kingdom and Europe who were eager to find out once and for all if there was indeed snow in the middle of Africa.

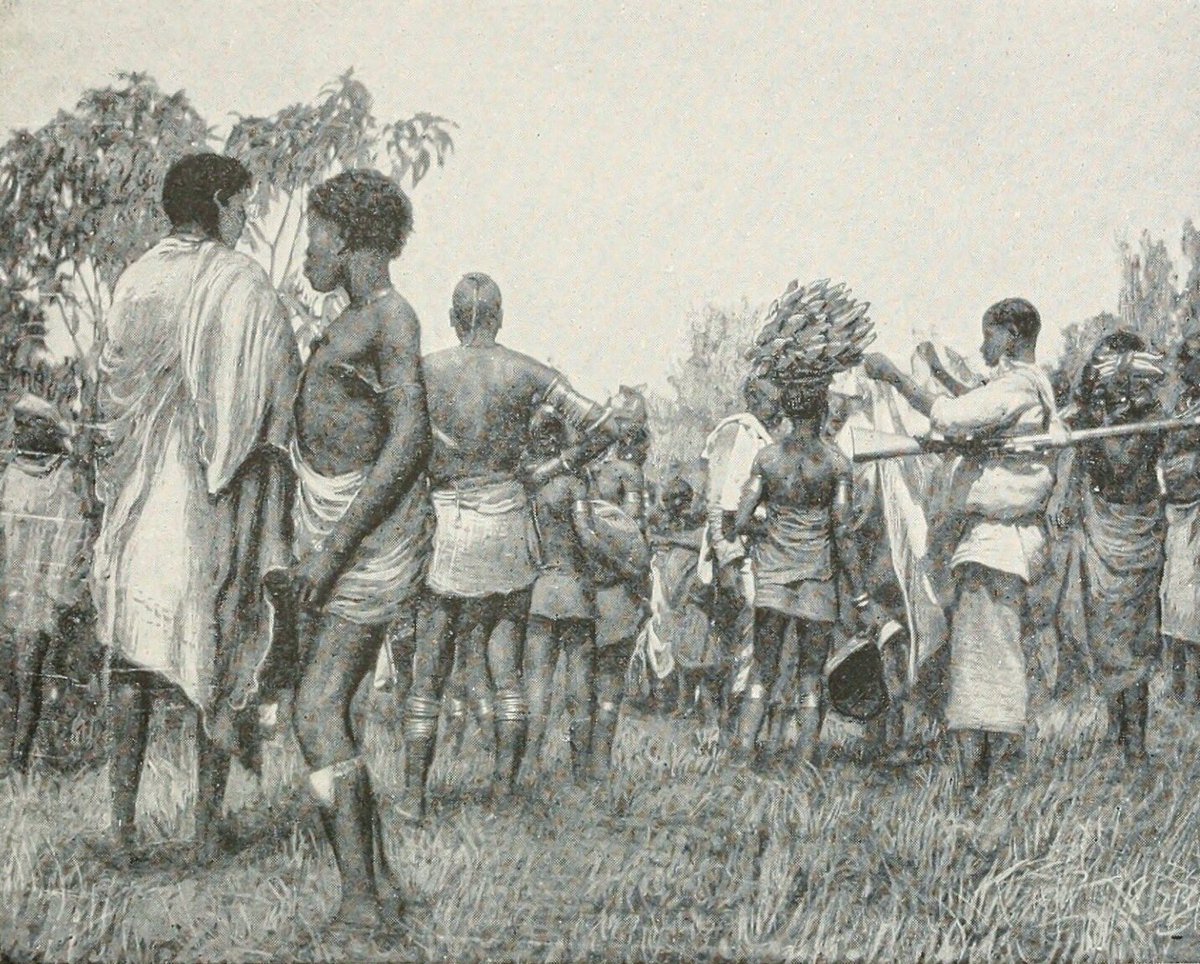

13/53 Days to his expedition, Johnston gathered supplies and planned his trek. He had a few Zanzibari porters with him. His Tamil assistant, Virapan, besides him, he recruited a few more from Mombasa and Rabai. In all, he managed to secure 120 porters.

14/53 As he contemplated his trudge towards Kilimanjaro, Johnston must have been wary of a number of things. If he wasn’t fretting about debilitating fevers of the type to cause visions of the Swiss alps in Africa, then the prospect of encountering...

15/53 ...bloodthirsty tribes in the East African nyika was definitely petrifying.

16/53 Sir Hamilton intended to reach Kilimanjaro through Taita country, using this actual route that he devised with others. While he did manage to reach Kilimanjaro, Johnston gives us a glimpse of some of the tribulations he underwent enroute.

17/53 These are captured in a book he published in 1886 called The Kilimanjaro Expedition.

18/53 In the book, we learn that Johnston had a disliking for porters who hailed from Mombasa and Rabai. He describes in a fond way how his Zanzibari porters were subservient and courteous, and how, contrariwise, those from Mombasa and Rabai “yawned...

19/53 ...unrestrainedly in my face when I questioned them...”

20/53 Johnston went on to write the following about the Mombasa and Rabai porters:

21/53 “But truth must be told, and in the interests of travellers who succeed me in these districts, I warn them, if they can help it, never to engage porters at Mombasa. Independently of all questions of religion -Mohammedan and Christian alike—the...

22/53 ...inhabitants of the Mombasa district are a thoroughly bad lot. It is hopeless to win them by kindness, or infuse a spirit of discipline by sternness. They are liars, cowards, thieves, and drunkards. They were so when Krapf, the earnest pioneer of...

23/53 ...Christian missions, first came among them; they are so still, after nearly forty years of evangelization. Why is it that men got from Zanzibar, Pangani, Mozambique, or elsewhere, should be so much superior? It must be some inherent fault in the local...

24/53 ...race, because the few men whom I obtained from the Mombasa missions that were not natives of Mombasa, but had been trained in the mission schools, turned out all that could be desired...”

25/53 Once after Johnston’s caravan had left Rabai enroute Maungu, he was forced to assert his authority on the porters by corporal means.

26/53 His porters were instructed to march to Gora, some 30 miles from Mombasa. Here, they would find and replenish their supplies of water. He gave his caravan a little start ahead and followed a kilometer or so behind in a hammock. He felt weak from fever to..

27/53 ...be able to go on foot.

28/53 A few hours later, he caught up with his porters enroute. They were leisurely reclined under the benevolent shade of a massive tree. Concerned, the explorer sought to know from his headman, whom he described as a christian, why the men rested the way...

29/53 ...they did.

30/53 The headman explained that the march to Gora was a long one given the time of day.

31/53 Johnston wasn’t going to accept this defiance. He snapped at his headman, telling him that only he had authority to decide when it was time to halt, that the morning was still fresh, and that if they rested, they would not be able to reach the water...

32/53 ...place by sunset.

33/53 Amid “murmurs of dissent” and “sullen looks from the porters”, they stood their ground. The more submissive Zanzibaris stood quietly together awaiting the outcome of the dispute.

34/53 Johnston feared that capitulating to the inclinations of the group of rebellious porters would put into jeopardy the entire Kilimanjaro. He ordered a hole to be sunk at the centre of the clearing, and into which the loads were placed.

35/53 He then randomly picked out one porter and ordered him to pick up his load and hit the road. No sooner had he refused than Johnston, snatching the porter’s walking stick, furiously whipped him with it. Virapan, Johnston’s Tamil deputy, grabbed the...

36/53 ...screaming porter by the heels to secure his boss’s maximum flogging effect.

37/53 The rest of the men promptly “hoisted their loads on their bullet-heads, and were falling into file along the narrow path, leaving my servant and myself alone with the victim of our wrath”, Johnston wrote.

38/53 They reached Gora just after sunset although Johnston had to wait to pitch his tent as some of his porters lagged behind.

39/53 From here, they set off towards Samburu and onwards to Mwatate.

40/53 Only after Johnston parted with presents “for passing through our country and drinking our water” did the natives of Mwatate allow the caravan to pass through their country. The expedition team trudged through Taita country and Lake Jipe, where Johnston...

41/53 ...stumbled on lots of game, some of which he shot at for sport and meat alike.

42/53 He spent the penultimate leg of his Kilimanjaro expedition among the Taita. To conclude, this is how the explorer described his time with the Taita:

43/53 “Firstly, their hair was generally worn in long strings, where the wool was stiffened with fat and red clay into a number of rats’ tails. There were generally one or two incisors knocked out in the upper jaw, the lobes of the ear were enormously...

44/53 ...distended with wooden cylinders or rings, and lastly, the Wa-Taveta, like most of the natives of Inner Eastern Africa (and unlike those of the West), were totally ignorant of what we call decency.

45/53 I would like to express this more delicately by saying that they were innocent of all clothing, but this was not the case, as many of the inhabitants wore cloth, or skins, round their shoulders, either for adornment or when the weather was chilly with...

46/53 ...breezes blowing off the snow-capped mountain.

47/53 I felt at home with the Wa-Taveta from the first, for they were thoroughly conversant with Swahili, the coast language—the French of Eastern Africa, and as I also knew this tongue we had at once a medium of ready communication. So the natives who had come..

48/53 ...to meet our caravan, and trotted along by my side to direct me to the accustomed camping-place, chattered as we went and not only asked for, but imparted, information.

49/53 One of the first questions was, ‘What is your name, white man?’

50/53 ‘Johnston’

51/53 ‘Jansan?’ they shrieked laughingly.

52/53 ‘Why, you must me Tamsan’s (Thomson's) brother....’

53/53 Mr. Joseph Thomson, on his way to Maasailand, had passed through Taveta, leaving a very pleasant impression behind him (You can find a separate story on this on my HistoryKe Facebook page).

Correction: Northern Rhodesia = Zambia.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh