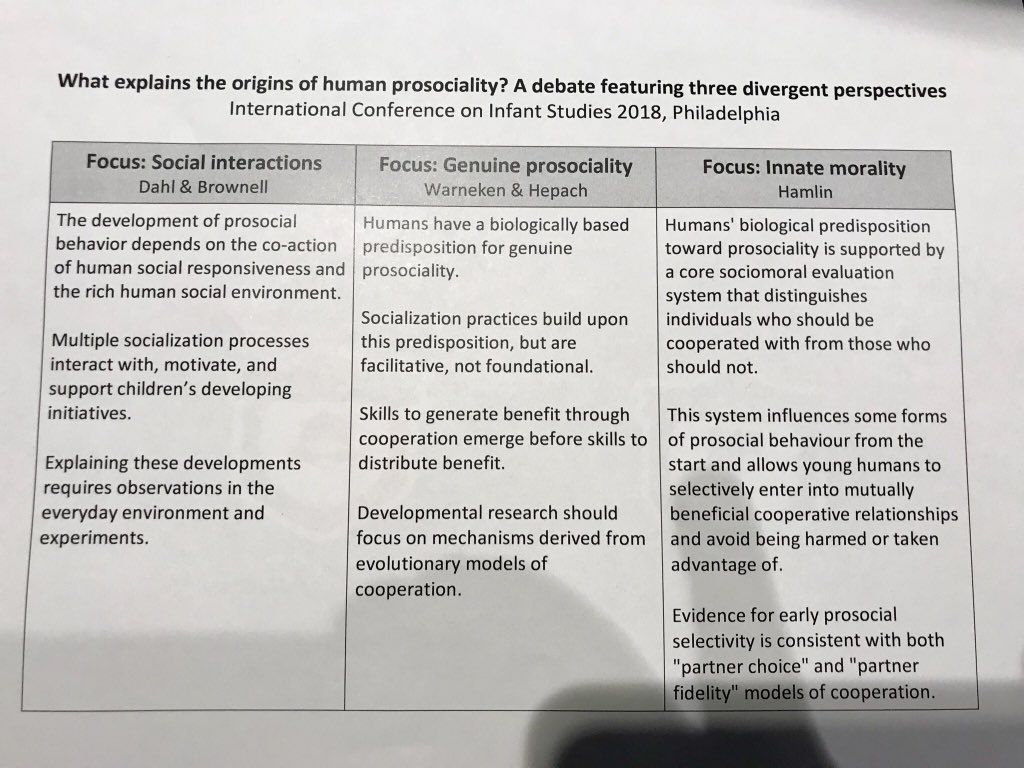

Prosocial development throwdown at #icis18: presentations by Audun Dahl, Felix Warneken, and @JKileyHamlin. Three opinions on a fascinating topic! [livetweet thread]

Dahl up first. Puzzles of prosociality: there’s an amazing ability to help others prosocially from an early age, but some infants don’t! Why? Behaviors emerge via 1) social interest and 2) socialization.

Framework of co-action. Starting with early turn-taking and contingency, caregivers scaffold social interaction. They even encourage and facilitate helping behaviors.

This socialization increases early helping: encouragement, praise all facilitate prosocial behavior, both observationally and experimentally.

Last point is methodologically. We need naturalistic data to study changes in everyday behavior. But we need causal evidence from experiments.

[Btw, I called this a “throwdown” but it’s clearly super collegial - down to the shared handout that I posted earlier. All three of these folks are really nice people. Felix right now is showing photos of his collaborator’s daughter.]

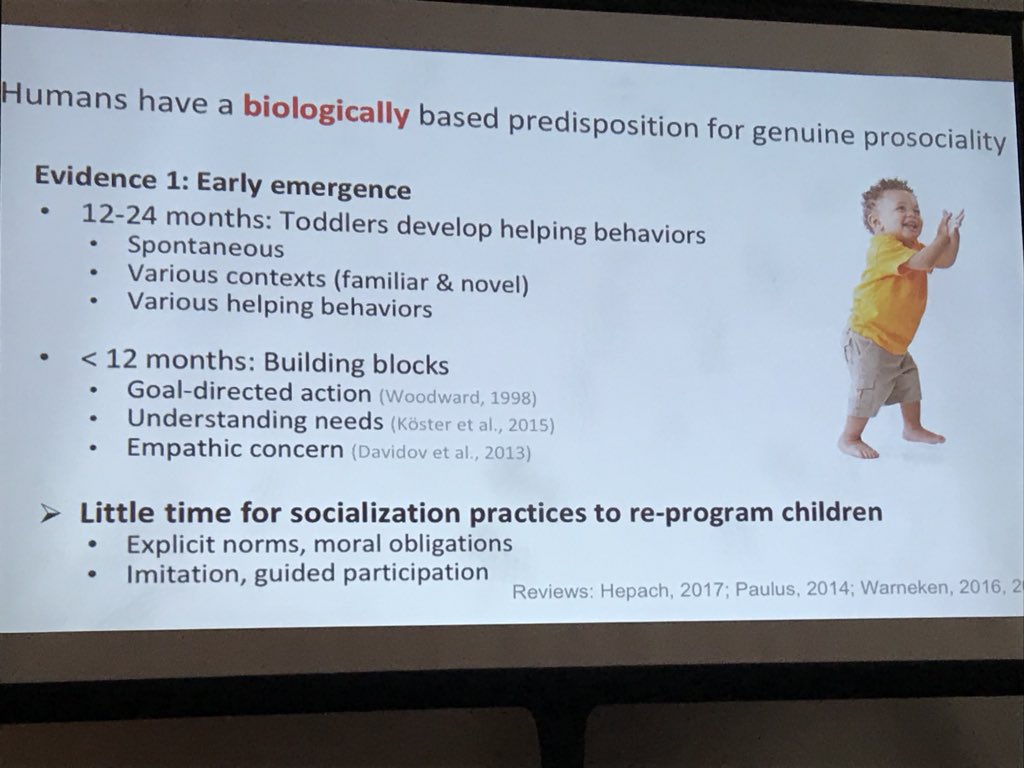

Warneken up next. Humans have a biologically based predisposition for genuine prosociality. Seeing others’ needs being fulfilled is intrinsically motivating. Many alternative explanations don’t hold up.

Where does this come from? Not socialization alone, it’s biological. Received story is that babies need “reprogramming” so they don’t act selfishly [from Freud], but that’s not the right approach. Kids have a social inclination and socialization builds on it.

Cross-cultural data supports this claim as well. Toddlers help wherever we have looked. But this approach is limited because you can always tell a socialization story.

Furthermore, comparative evidence is really important. Chimps and bonobos don’t socialize their offspring but they still show the roots of prosocial behavior. So biology provides the building blocks.

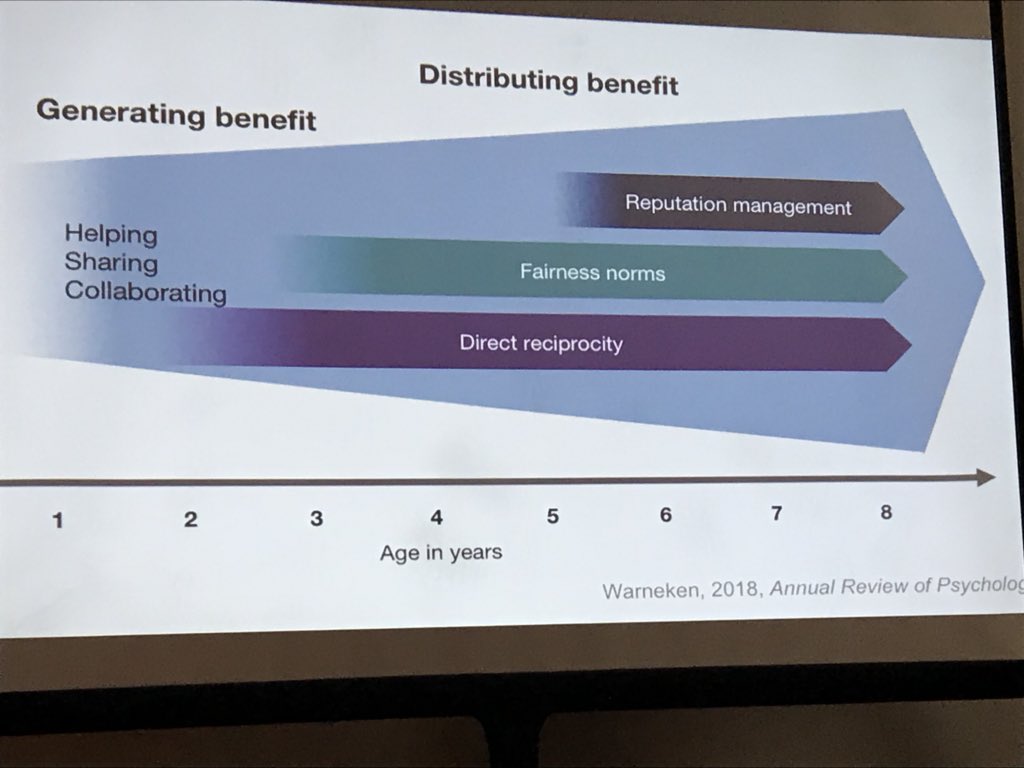

The developmental challenge is to understand changes in prosociality behavior. For example, different forms of reciprocity emerge at different times and with different cognitive prerequisites.

[editorial comment: both speakers so far have talked a lot about the role of methods in documenting developmental process, but there hasn’t been any talk about stability of measurement, which is critical for understanding variability across cultures and individuals. ]

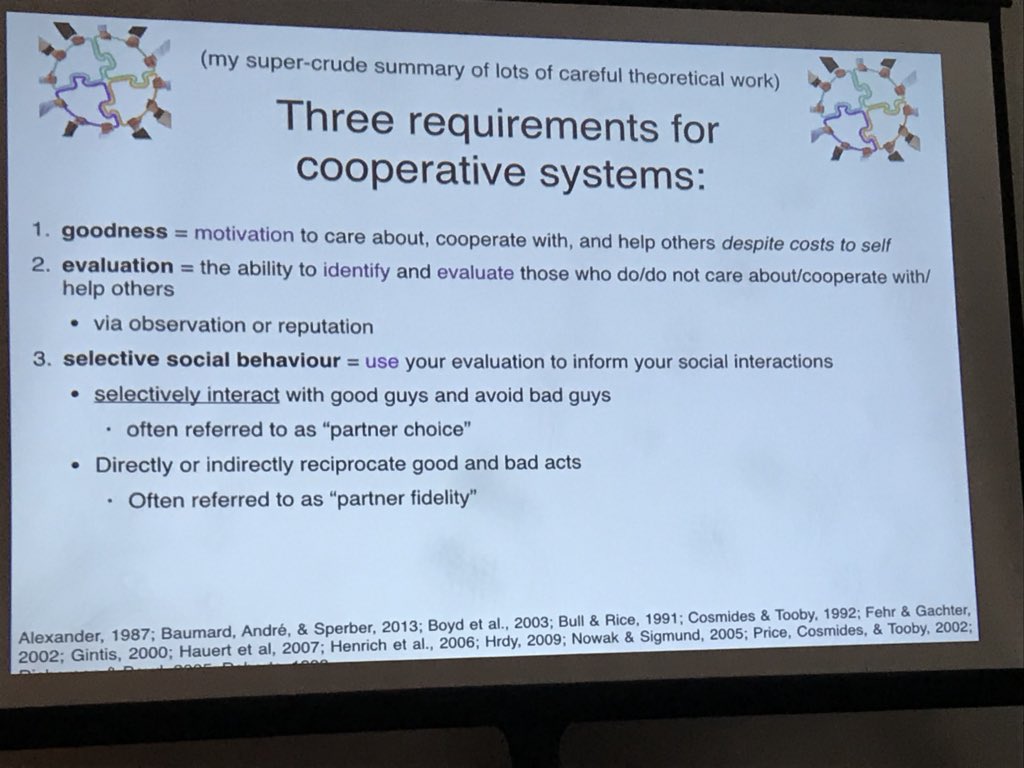

Here’s @JKileyHamlin. Is early prosocial behavior selective? This adds nuance to the question beyond “are babies prosocial?” If you don’t have 2 and 3 (below) you can’t have 1 and so prosocial behavior would be useless.

There’s lots of evidence for social evaluation in infancy (though the replication picture is complex [good to mention this!]. But it still could be that babies are “indiscriminate altruists.” [warneken view] OR they could be “selective altruists” [hamlin view].

Behavioral evidence with helping tasks shows that older kids are selective. BUT Hamlin is going to present evidence that babies *are* selective.

In first person and third person situations, there is evidence for babies (2 and under) preferring to help a prosocial actor.

In sum, this is a stronger nativist position, where Hamlin buys Warneken’s biological basis but adds a second innate component: te ability to evaluate so that you can get the social system working and avoid free-riders.

[this is an amazing group of talks - clear, coordinated, and fascinating. So glad I went to this session.]

Question period had been fascinating. One theme is asking about alternative populations where prosocial behaviors might be less socialized or less adaptive (eg resource scarcity, at-risk kids, etc).

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh