This phenomenon - when you look away from a moving thing, and you briefly see illusory motion in the other direction - is the "Motion Aftereffect," and it comes from some very basic brain maneuvers. Who wants to join me on going full #NeuroThursday here? en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motion_af…

https://twitter.com/ceruleancynic/status/1014311085762019328

Most neurons in the brain (and elsewhere) do this thing called "adaptation," where they accept whatever's going on as the new normal. For example, if you sit down with your laptop on your lap, you'll soon stop noticing the weight.

This can arise from the crudest single-cell level: some ion channels in the cell membrane have negative feedback loops that self-dampen.

Adaptation is super useful. There are a lot of variants and theories, but think of it as a mechanism to keep the meter from getting "pinned." If your mechanism (neuron) has a limited range, you can cover anything if you're willing to keep recalibrating around whatever arrives.

So if you stare at a moving object for a little while, your brain* recalibrates to that motion. It says "Leftward flow is the new normal, got it." Then you look at an unmoving object, and your brain says, "This is moving rightward compared to normal!"

(Oh hey, what's that asterisk? Is something neurosciency gonna get MORE COMPLICATED? You betcha!)

That little voice in the earlier tweet might be in your brain - there are plenty of secondary visual areas (especially ones called V3A and V5) that detect motion, and thus could be the ones adapting here.

But that voice might also be in your eyes. As I've discussed before, your eyeballs do a lot of fancy footwork. (Eyework?) I talked about it before in the context of slow/solstice vision.

https://twitter.com/BenCKinney/status/944026526890196992

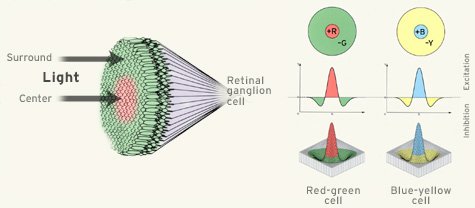

Those eyeball network cells ("retinal ganglion cells") do a lot of visual preprocessing. Here's an image of them doing color contrast. Looks complicated! But the gist should be clear...

...these retinal ganglion cells combine information from a bunch of your light-sensitive cells. You can (hopefully) see how that might be enough to detect motion.

So to make a long story only as long as necessary: motion-sensitive retinal ganglion cells might be the ones producing the motion aftereffect.

And lo, a #NeuroThursday (NeuroTuesday?) lesson for you home #neuroscience fans: sometimes, the cause of a big conscious perceptual phenomenon is a little cellular recalibration property.

Thanks, world! If this helped you adapt to the scroll of your twitter feed, share this around, or check out my other work! benjaminckinney.com/publications/

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh