For our second #Pride2018 thread, let's delve a bit deeper into same sex bug hookups.

Same sex mating, like in the picture below, has been studied pretty intensely in bed bugs, but also in the Fruit fly Drosophila.

So let's talk a little bit about Fruitless!

#DeepDive

Same sex mating, like in the picture below, has been studied pretty intensely in bed bugs, but also in the Fruit fly Drosophila.

So let's talk a little bit about Fruitless!

#DeepDive

Fruitless is an insect-specific gene which turns on the developmental pathways needed for mating behaviors to happen in insects.

There's no equivalent in humans, so there's not really a way to make comparisons.

There's no equivalent in humans, so there's not really a way to make comparisons.

In fruit flies, sex determination is...weird. They don't have the same system we have.

In fruit flies, it's the ratio between the sex chromosomes and the non-sex chromosomes which is important. 1:1 sex:nonsex is female; 1:2 sex:nonsex is male.

It's...a bit wonky.

In fruit flies, it's the ratio between the sex chromosomes and the non-sex chromosomes which is important. 1:1 sex:nonsex is female; 1:2 sex:nonsex is male.

It's...a bit wonky.

Once these chromosomes are inherited, there's a complicated processing cascade which starts to form all the sex-specific features of the flies.

Two very important proteins in this are Sex-lethal and Transformer, both of which are spliced in sex-specific ways.

Two very important proteins in this are Sex-lethal and Transformer, both of which are spliced in sex-specific ways.

In the lab, we can manipulate this process by sticking different versions of the gene into different flies.

In males, we can put the female version into the genome and delete the male version.

In females, we can eliminate the sites on the gene which allow Transformer cutting.

In males, we can put the female version into the genome and delete the male version.

In females, we can eliminate the sites on the gene which allow Transformer cutting.

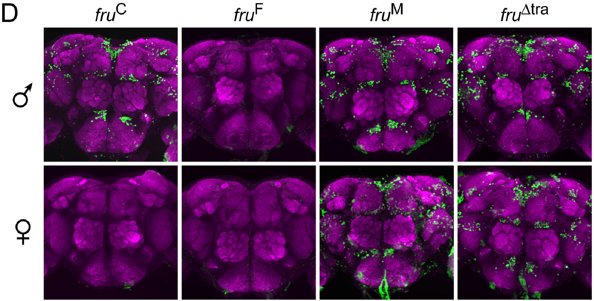

After the gene is spliced, we actually know where the protein is expressed in the brain. There are about 2,000 neurons with some sort of Fruitless activity, between male and female flies.

(Citation same as above)

(Citation same as above)

This is the standard way that people think about Fruitless.

After a period of isolation, if you house male flies together, you get a lot of 'chaining', the behavior seen in the first post.

After a period of isolation, if you house male flies together, you get a lot of 'chaining', the behavior seen in the first post.

In the figure above, the flies were isolated for about a week after emerging. They were then either paired with same-sex flies, or female flies.

The Fru mutation-which has been snipped and driven using a genetic driver (LexA)-results in a lot of male/male courting.

The Fru mutation-which has been snipped and driven using a genetic driver (LexA)-results in a lot of male/male courting.

So...it's generally accepted that Fruitless is needed for male/female courtship. If you delete it in the flies, they either don't court or court only males depending on the mutation.

However...most of the studies which produced this data raised the flies in isolation.

However...most of the studies which produced this data raised the flies in isolation.

It turns out that there are some aspects of courtship which are actually learned.

If you house male fruitless mutant flies in groups with females, and allow them to contact each other, you get a more indiscriminate pattern of mating.

If you house male fruitless mutant flies in groups with females, and allow them to contact each other, you get a more indiscriminate pattern of mating.

The figure above shows that you can get nearly equal mating if you keep the flies with groups of females, in conditions where they can both see *and* contact the females.

It turns out that in those neurons which express Fruitless, there's another gene which is expressed.

This gene is called Doublesex, and it's also sex-specifically spliced by Transformer.

However...there's a problem. Unlike Fruitless, Doublesex is made in all parts of the fly.

This gene is called Doublesex, and it's also sex-specifically spliced by Transformer.

However...there's a problem. Unlike Fruitless, Doublesex is made in all parts of the fly.

This problem is actually really easy to solve, because we know so much about Drosophila genetics.

There's a driver called c155 which we can use to cause the brains of the male flies to express massive amounts of the female-specific transformer protein in a brain-specific way.

There's a driver called c155 which we can use to cause the brains of the male flies to express massive amounts of the female-specific transformer protein in a brain-specific way.

C155 pushes the female version of Transformer into the heads of male flies expressing the female version of Fruitless.

The female version of Transformer causes female Fruitless, as well as female Doublesex.

Male flies with these female proteins don't court.

Like, at all.

The female version of Transformer causes female Fruitless, as well as female Doublesex.

Male flies with these female proteins don't court.

Like, at all.

So...female splicing of Fruitless causes male flies to court other males, or to indiscriminately court.

Whether Fruitless mutants court males, or court indiscriminately, depends on their social environment while learning how to court.

Whether Fruitless mutants court males, or court indiscriminately, depends on their social environment while learning how to court.

A second gene, called Doublesex, appears to regulate these acquired courting behaviors.

There are innate and learned aspects of insect mating behaviors...and in one species, we know the genes responsible for each of these processes.

It's a long road to using this knowledge to disrupt mating in-say, disease vectors, but we now understand the process a lot better.

It's a long road to using this knowledge to disrupt mating in-say, disease vectors, but we now understand the process a lot better.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh