1. Today’s report by the Justice Committee into disclosure failings in the criminal justice system is absolutely damning. To save you reading in full (although you should), here are the highlights. [THREAD]

https://twitter.com/CommonsJustice/status/1020082104212819968

2. As for what disclosure is and its importance, see my thread here from last year:

https://twitter.com/barristersecret/status/887191568158994432?s=21

3. In short, disclosure is one of the most important parts of the criminal process. The state providing the accused with material which may reasonably undermine the prosecution case or assist the defence case. It is central to avoiding miscarriages of justice.

4. There is a sorry history of disclosure failings stretching back years, if not decades. Report after report (6 in the last 6 years) has pointed this out.

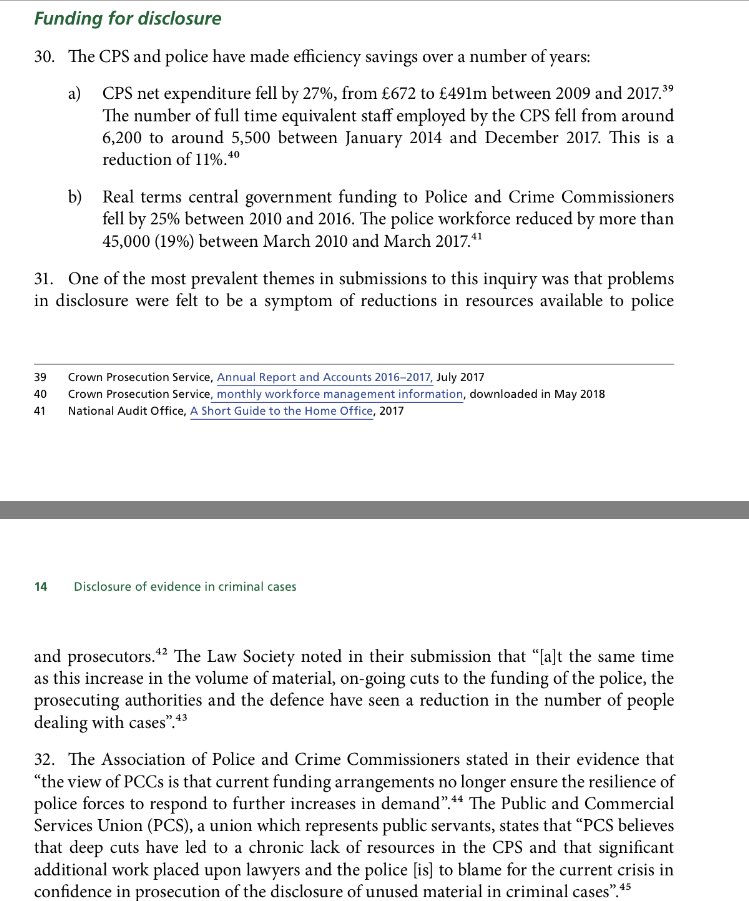

5. Part of the problem is lack of resources. Huge cuts to CPS budgets and staffing levels, huge cuts to the police and huge cuts to legal aid. #TheLawIsBroken #ItsAllInTheDamnedBook

The Committee has said that funding *must* be reviewed by government.

The Committee has said that funding *must* be reviewed by government.

6. Part of the problem, however, is cultural. Too often disclosure is seen by police officers and the CPS as a “bureaucratic bolt-on”. A box-ticking irritant, rather than central to ensuring justice.

7. This attitudinal problem is critical, and is hinted at by the staggering complacency of the outgoing Director of Public Prosecutions, Alison Saunders, who comes in for serious personal criticism in the report. Read these comments. This is resignation-grade failure.

8. Note also this dig at the CPS obsession with conviction statistics, compared to the attitude to disclosure.

9. The CPS is criticised for not properly recording disclosure failings, and therefore underestimating the prevalence of disclosure failings by up to NINETY PER CENT.

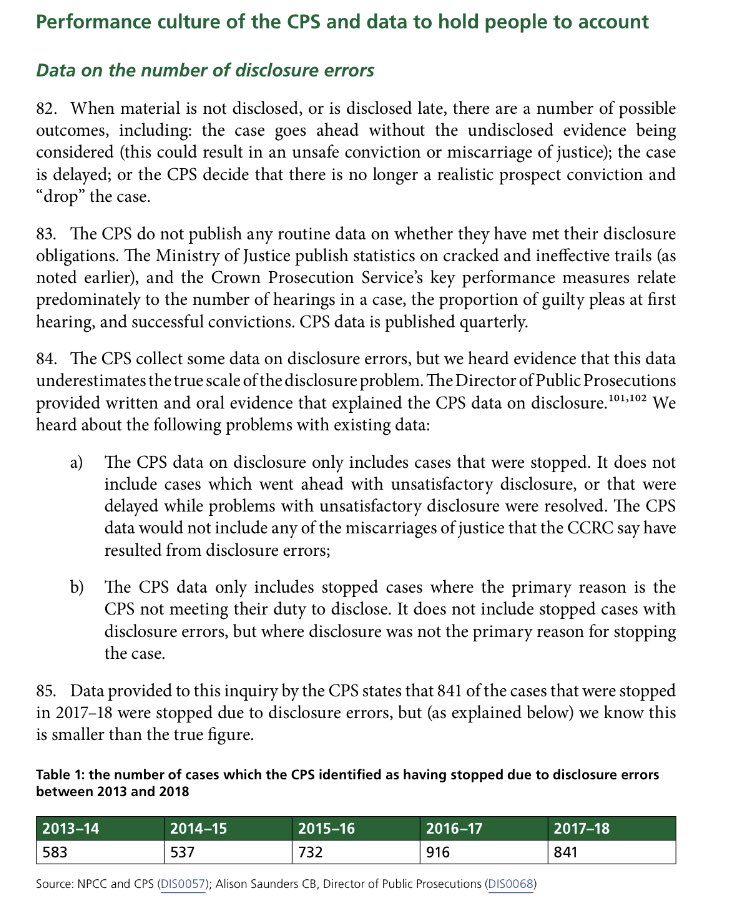

10. Even with that underestimate however, the number of cases recorded as collapsing for disclosure reasons has soared by 40 per cent in four years.

11. The Attorney General has overall responsibility for the CPS. The outgoing AG (Jeremy Wright QC, recently shunted to Culture) was also, like his predecessors, asleep at the wheel:

12. Away from the CPS, police culture - a failure to appreciate the importance of disclosure - remains a problem.

13. Another problem is the challenge posed by the increase in digital material collected in criminal investigations, such as mobile phone evidence. There is a clear need for further guidance on how to approach this issue (and the implications for privacy of complainants).

14. A final thought for magistrates’ courts. The report, and recent media attention, has been on Crown Court (usually sex) cases. But disclosure failure is rife across the system. The DPP ludicrously claimed magistrates’ courts are better. They are far, far worse.

15. The report concludes by setting out a number of recommendations. I’ll leave you with this as I mount my hobby horse and ride into the sunset. [ENDS]

Apparently the link to the report isn’t working. Try this:

https://twitter.com/commonsjustice/status/1020227821866766336?s=21

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh