In 1989 the BBC killed off #DoctorWho. The corporation said the series was being 'rested'; the fans suspected it was dead as an Adric. But then an unlikely saviour emerged to carry #DrWho through the wilderness years.

This is the story of the Virgin New Adventures...

This is the story of the Virgin New Adventures...

Both Michael Grade and Jonathan Powell, BBC Directors in the 1980s, disliked #DoctorWho. They felt it was outdated, violent and cheap-looking. Ratings were awful, exacerbated by terrible scheduling. Relations with producer John Nathan-Turner had also hit rock bottom.

Grade had already paused the series in 1985, and insisted Colin Baker leave the show in 1987. By 1989, with Nathan-Turner ready to leave and script editor Andrew Cartmel already gone, Jonathan Powell pulled the plug on the whole thing.

#DoctorWho has one of the oldest and most passionate fandoms in television, and many fans had felt that the series was finally going in the right direction, with a darker and more mysterious Doctor and an assistant who was finally being given a more mature role.

Whovians had also produced a lot of fan-fic and critical analysis of #DrWho, and a number of fans were themselves budding or actual writers - often due to their love of the series. So there was still a core audience out there.

Which was lucky for Virgin Publishing, who had purchased Target Books in 1989. As the main publisher of #DoctorWho novels it was clear that with the series cancelled the flow of new books was going to dry up pretty quickly.

So Virgin's fiction editor Peter Darvill-Evans asked the BBC for permission to commission and publish new original #DrWho stories. With only Marvel UK still showing any interest in the show the BBC agreed. What did It have to lose? It was quite a gamble for Virgin though...

...but believing the fan base was there, and with a number of writers familiar with novelising #DoctorWho stories, they had high hopes the gamble would pay off. Provided the material was what the hard-core Whovian fandom were after.

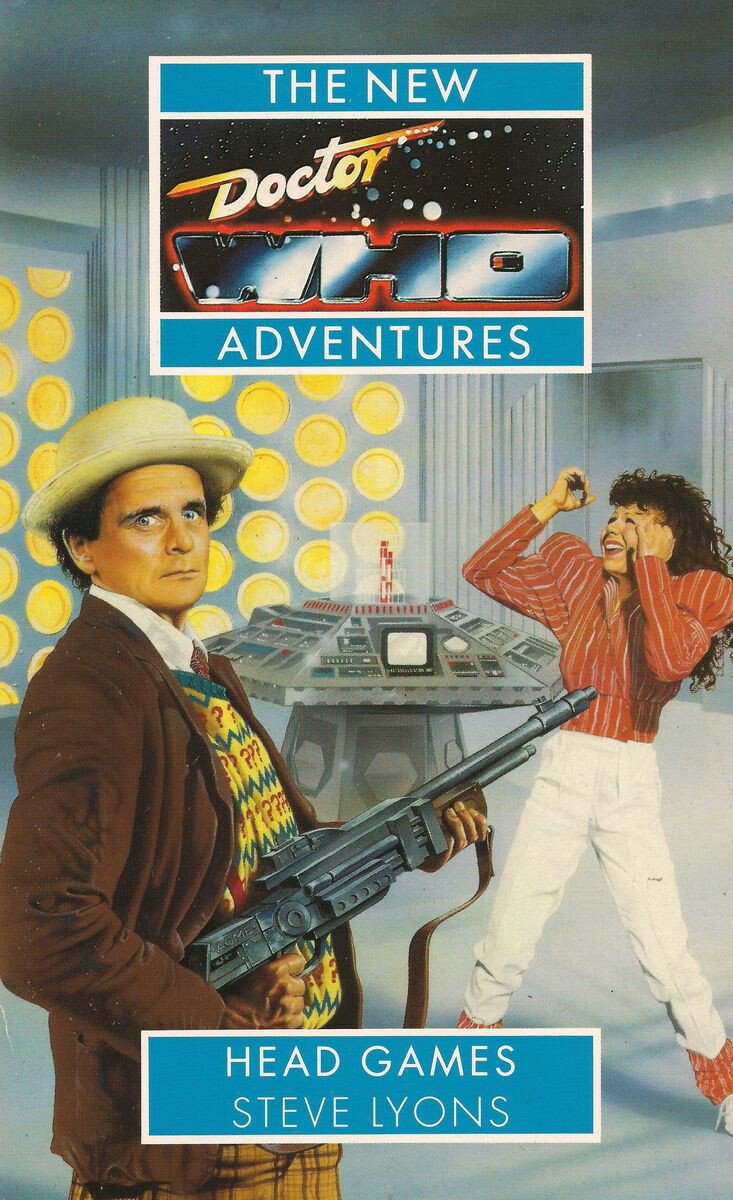

Running from 1991 to 1997 the New Adventures would eventually consist of 61 novels focused (almost) exclusively on the Seventh Doctor. Target stalwarts such as John Peel and Terrance Dicks were brought in to kickstart the series.

But the New Adventures also brought in passionate fans looking to launch their own writing careers. Both Paul Cornell and Mark Gatiss wrote for the series, and the New Adventures helped launch the careers of Kate Orman and Justin Richards.

And with no BBC executives policing the stories the New Adventures could go where they liked! New assistants, new aliens, even a new back-story for the Doctor were all suddenly possible.

Cover art for the New Adventures could be variable. The ever-excellent Peter Elson did a few, but other artists fared less well with some of the cover work.

There were of course critics of the New Adventures. Adult-oriented #DoctorWho was not for everyone; the plots could be ridiculously complicated; the character of Ace sometimes bordered on fan-fantasy projection...

...yet there were some cracking stories in the New Adventures, not least Paul Cornell's Human Nature - later to be adapted as a new #DoctorWho story when the series returned.

In 1994 Virgin began publishing The Missing Adventures series, adult-oriented #DoctorWho stories featuring earlier Doctors. The New Adventures character Bernice Summerfield also got a spin-off series of books.

But it couldn't last. In 1996, following the #DoctorWho movie, the BBC did not renew Virgin's licence and instead decided to publish its own line of original #DrWho novels. After 61 New Adventures and 33 Missing Adventures the Virgin series ended.

The New Adventures did an important job keeping #DoctorWho alive and fresh in the 1990s. They showed it could be complex, dark, hard sci-fi and that there was an audience for this kind of Doctor. They undoubtedly influenced the rebooted TV series.

But for me the New Adventures were genuine pulp sci-fi. New writers were given old themes and asked to turn them quickly into amazing stories. If quality varied, well that's pulp. But the legacy of the New Adventures should not be overlooked.

More stories another time...

More stories another time...

Postscript: as a teenager I was interviewed on local radio, having organised a petition to 'Save #DoctorWho.'

I neglected to tell the interviewer I had only managed to gather four signatures...

I neglected to tell the interviewer I had only managed to gather four signatures...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh