This #ClassicalZooarchaeology thread is about ancient Greek sacrificial feasting. I want to focus on what the animal bones can add to our understanding of this important topic. While there are several good overviews of sacrifice in texts & art, bones offer new perspectives

/1

/1

Sacrificial ritual was associated with Greek polytheism, which was extremely diverse & constantly changing. So, sacrificial ritual was pretty diverse across time and space

If you want an intro to Greek polytheism, you can also check out the thread below

If you want an intro to Greek polytheism, you can also check out the thread below

https://twitter.com/FlintDibble/status/1013869173355708416

Instead of going into exceptional sacrifices (next month, I’ll do a thread on dog sacrifice when @ASCSAPubs publishes the Agora Bone Well), this thread focuses on the canonical bones burned for the gods. The advantage w/ this focus is it’s easy to combine texts, art, and bones

/3

/3

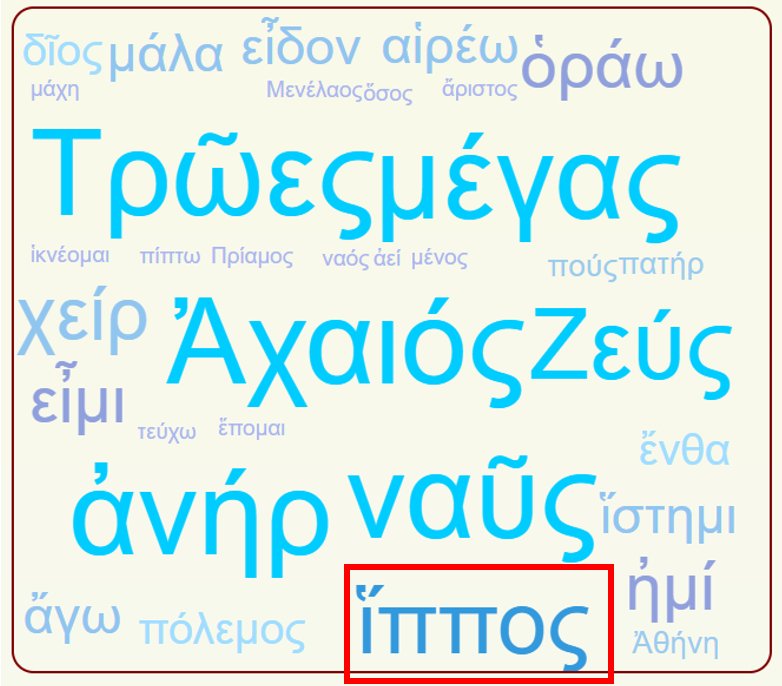

If you’ve read Homer’s Iliad & Odyssey, you know that Greek heroes liked to eat their meat. Before the feast, they’d burn the thighbones wrapped twice in fat for the gods

Odysseus brags “No human ever burned so many thigh-bones for the Lord of Thunder” transl. @EmilyRCWilson

/4

Odysseus brags “No human ever burned so many thigh-bones for the Lord of Thunder” transl. @EmilyRCWilson

/4

Hesiod explains why: Prometheus tricked Zeus

P. sorted the parts of a slaughtered ox into 2 groups: the meat hidden in the ox’s stomach & the bones wrapped in “glistening fat”

Zeus chose the more appealing “glistening fat” over the unappealing stuffed stomach

Who wouldn’t?

/5

P. sorted the parts of a slaughtered ox into 2 groups: the meat hidden in the ox’s stomach & the bones wrapped in “glistening fat”

Zeus chose the more appealing “glistening fat” over the unappealing stuffed stomach

Who wouldn’t?

/5

Zeus was mighty pissed off when he saw he only got fat-wrapped bones

Hesiod concludes “Ever since that, the peoples on earth have burned white bones for the immortals on aromatic altars”

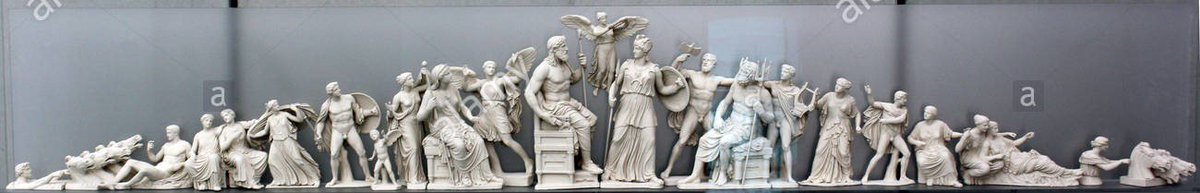

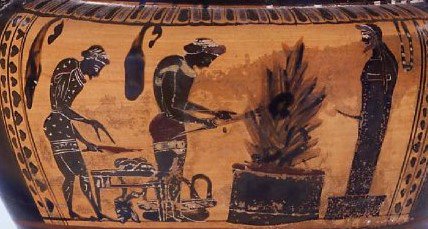

Greek vase paintings show this activity. The packet is likely fat-wrapped thighbones

/6

Hesiod concludes “Ever since that, the peoples on earth have burned white bones for the immortals on aromatic altars”

Greek vase paintings show this activity. The packet is likely fat-wrapped thighbones

/6

But it wasn’t just thighbones that were burned. Most vase paintings show a curling tail on an altar

Aristophanes jokes about a curled tail as showing “favorable omens.” Experiments show the tail always curls as it contracts. So, every time you burn a tail, it’s good luck!

/7

Aristophanes jokes about a curled tail as showing “favorable omens.” Experiments show the tail always curls as it contracts. So, every time you burn a tail, it’s good luck!

/7

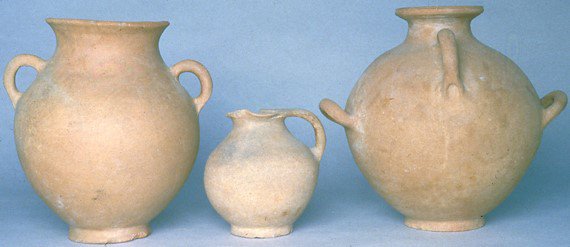

David Reese (1989) published a large group of burned hindquarters – mostly bones from tails, thighs & knees of sheep or goats – from the altar of Aphrodite Ourania in the Athenian Agora. Since then, zooarchaeologists have found similarly burned bones at Greek temples & altars

/8

/8

Kinda cool? Burned bones match ancient texts and art

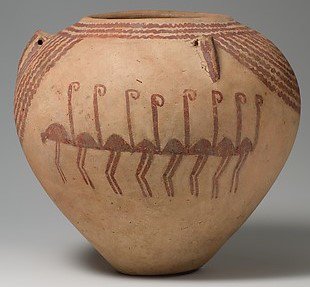

But the texts and art that describe ancient sacrifice are only as old as when the Odyssey and Iliad were first written down (750ish BC). Zooarchaeology shows us that selected groups of burned bones (= sacrifice) are older

/9

But the texts and art that describe ancient sacrifice are only as old as when the Odyssey and Iliad were first written down (750ish BC). Zooarchaeology shows us that selected groups of burned bones (= sacrifice) are older

/9

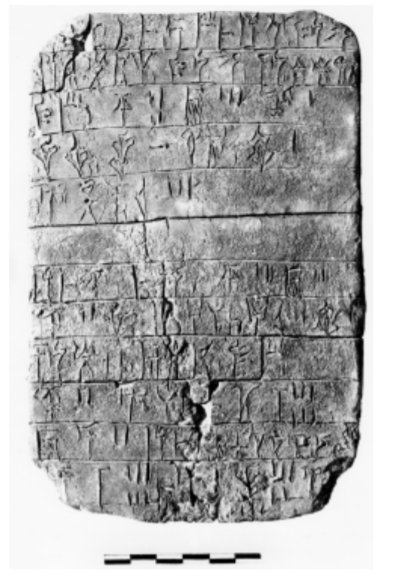

Earlier clay tablets in Linear B script (from 1200ish BC) record Bronze Age palatial feasts. The tablet below from Pylos lists a bull, 4 sheep, 100s of liters of wheat & wine, and smaller amounts of cheese & honey. Enough food “to feed over 1,000 people” (@DimitriNakassis)

/10

/10

These Linear B tablets don’t describe sacrificial ritual though

However, in the archives room of the Palace of Nestor at Pylos, Halstead et al, described a pit of burned bones from the thighs, forearms, and mandibles of at least 19 cattle and 1 red deer

/11

However, in the archives room of the Palace of Nestor at Pylos, Halstead et al, described a pit of burned bones from the thighs, forearms, and mandibles of at least 19 cattle and 1 red deer

/11

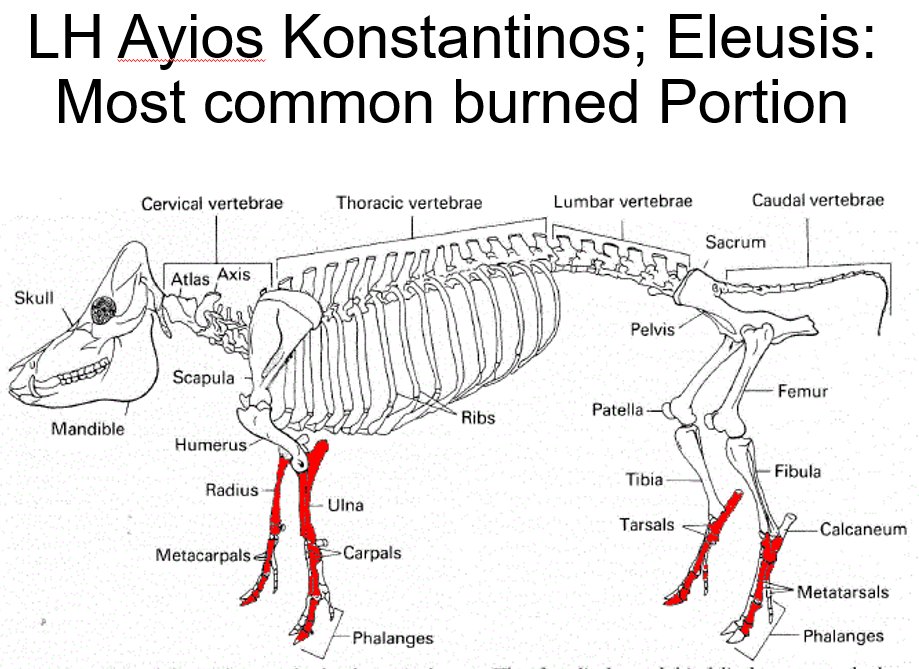

Burned bones from earlier Bronze Age sites show lots of diversity. While burned thighbones & tails have been found at a few sanctuaries (including the ash altar of Zeus at Mt. Lykaion), at others (Eleusis and Ayios Konstantinos at Methana), the lower legs were burned

/12

/12

I’ve been tracing this pattern of burned lower leg bones (sometimes found w/ head bones) in my own research. I’ve encountered these body parts burned and found in discrete deposits at Halasmenos (12th c BC), Nichoria (9th c BC), Azoria (7th-5th c BC) & Athens (4th-2nd c BC)

/13

/13

There’s only one textual reference to this type of sacrifice. In the Hymn to Hermes, the trickster god steals a herd of cattle from the other gods. To appease them, he sets a feast for each god. And to clean up he “destroyed all the feet and heads with the fire’s blast”

/14

/14

As more animal bones are studied, I think we’ll see more diversity in sacrificial ritual across different settlements and temples. For example, at the shrine to the Hero Opheltes at Nemea (6th-5th c BC), only the thighbones from the left leg of sheep were burned

/15

/15

This summer, I studied a large group of bones (6th c BC) from the Temple of Zeus at Histria, Romania. None were burned, but there weren’t any thighbones. These bones likely were food waste from the sacrifice

/16

/16

The butchery marks on the bones show an efficient procedure. In one area of the sanctuary, the animals were slaughtered and the less meaty parts were thrown away. The carcass was dismembered into larger units with cleavers and then broken down into smaller units with knives

/17

/17

Many texts record that priests were also sacred butchers. Butchery patterns show that these priests were professional butchers, using an efficient system to prepare large-scale sacrificial feasts. Priests were often rewarded for their skill with cuts of meat or animal hides

/18

/18

I think of a sacrificial feast as a spectacle. It started with a parade of animals to be slaughtered at the altar. The flames quickly engulfed the bones wrapped in flammable fat. And then the barbecue or beef boil began, with the smell and taste of meat washed down in wine

/19

/19

The role of the priest was front and center, never far from the victim or the feast’s preparation. But these feasts didn’t only perpetuate the hierarchy, they also strengthened group bonds as everyone feasted together on a regular basis

/20

/20

So, as you enjoy your summer barbecues, don’t just pour out a cold one for the gods below, make sure to wrap a bone twice in fat and throw it on the coals. The gods above subsist on this fragrant smoke. Plus, if those coals are hot, I promise it’ll make for quite a show!

/21

/21

Thanks for reading along. If you liked it, please retweet!

I’ve collected all the references and credits to images and publications in the thread below

I’ve collected all the references and credits to images and publications in the thread below

https://twitter.com/FDibbleCitation/status/1032300460978450432

And if you want to read more about ancient animals, check out my archive of #ClassicalZooarchaeology threads below

https://twitter.com/wfdibble/status/978941931714736133

For more on experimental studies of ancient sacrifice @ASCSAthens see "Burning Questions: An Investigation Into Ash Altars" by J. Morton and @diffendale

ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/news…

And also this awesome curling tail

ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/news…

And also this awesome curling tail

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh