#HistoryKeThread: The Handshake In Kano

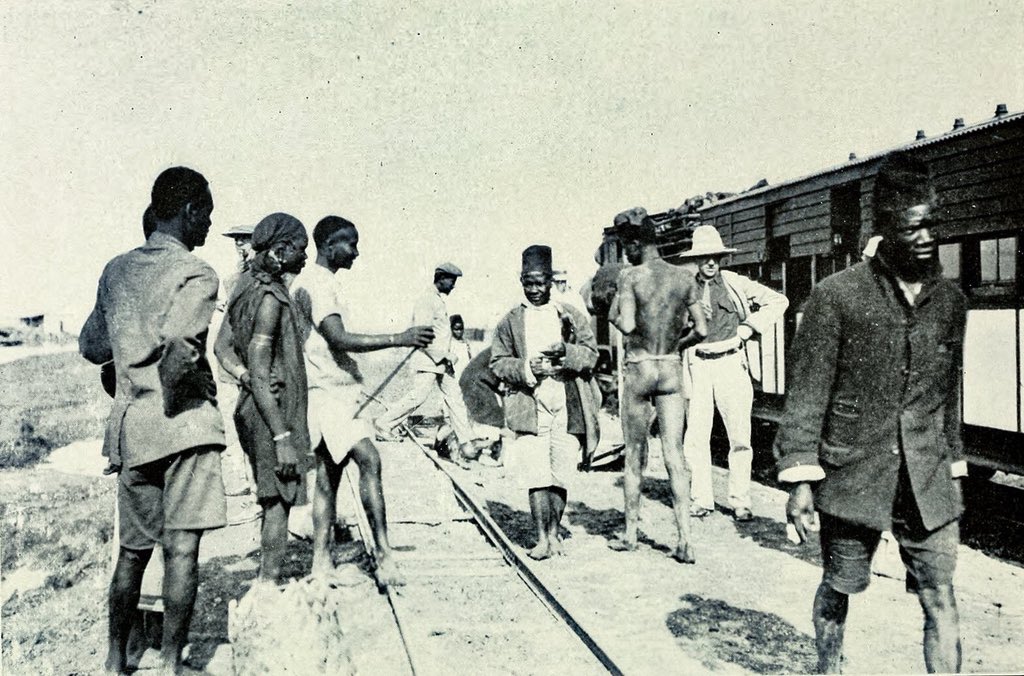

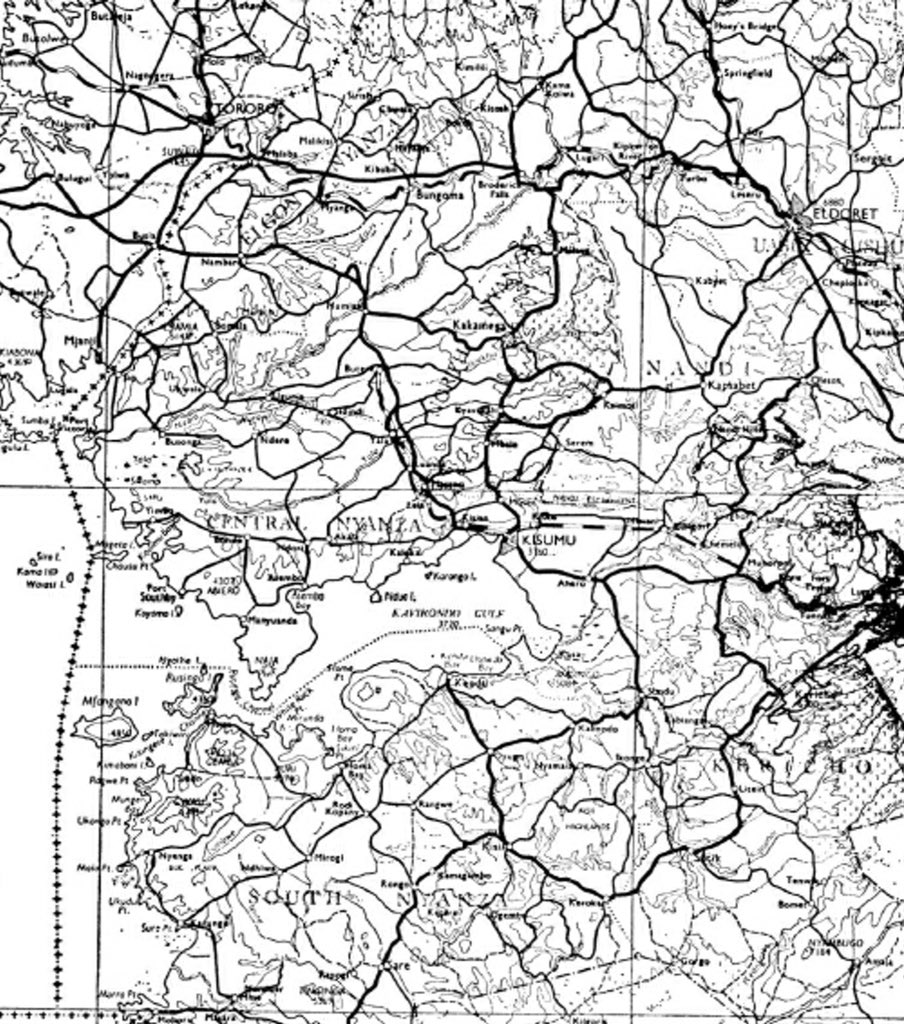

We know that the Uganda Railway was from 1896 called so because Kisumu, which was the destined railhead, was part of Uganda.

We know that the Uganda Railway was from 1896 called so because Kisumu, which was the destined railhead, was part of Uganda.

Even as part of then Uganda, large swathes of western Kenya as we know them today were collectively referred to as the Nandi Protectorate.

On 1st April 1902, the Nandi Protectorate, incorporating Kisii and Luo Nyanza, Luhyaland and greater Nandi country, was transferred to East Africa Protectorate. The resulting province was given the name Nyanza, although I am not sure how the name “Nyanza” came about.

The colonial authorities drew up boundaries that bound Luo, Luhya, Kisii and Nandi enclaves.

Shortly thereafter, East Africa Protectorate was renamed Kenya.

Shortly thereafter, East Africa Protectorate was renamed Kenya.

Despite this move, the natives of Nyanza still looked towards Uganda, according to the late Oginga Odinga in his book, “Not Yet Uhuru”.

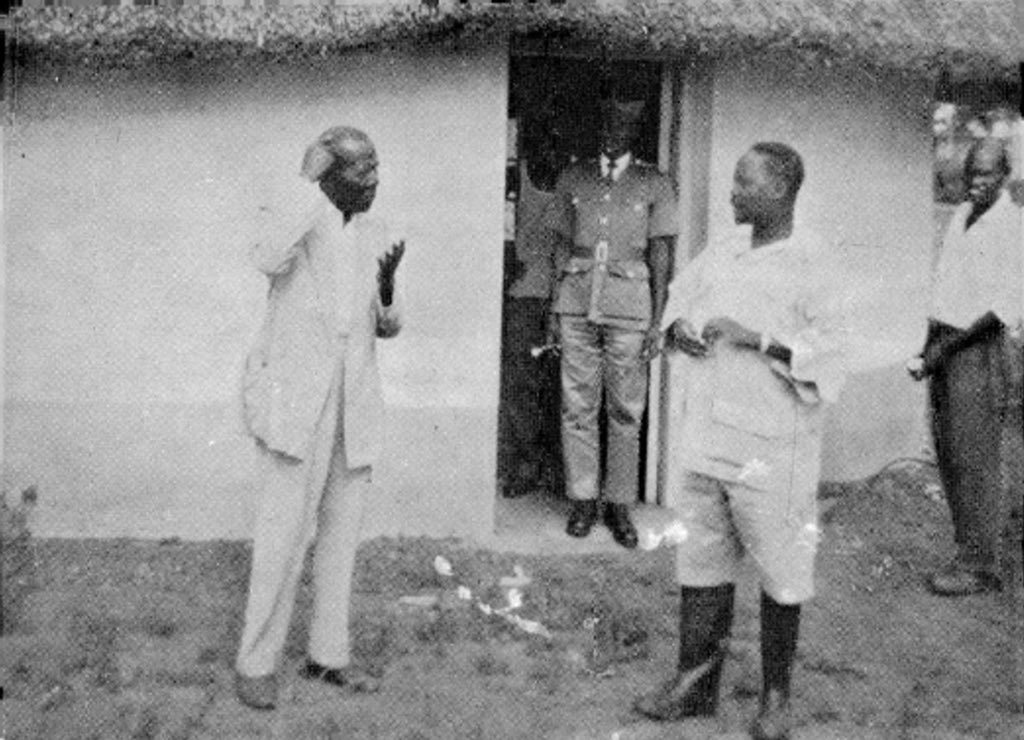

Oginga, seen here chatting with Ker Joel Omer of Sakwa sometime in the 1950s, described how Arabs (I suspect these were waswahili afro-arabs from Kenya’s coast) passing through Nyanza country heading coastwards from Uganda created a sense of alarm among the Luo.

The Arabs warned that the Luo were “part of a colony, meaning you have no land...the land belongs to the King of England...”

Soon, the British would, in 1900, introduce hut tax. It then dawned on the natives what the Arabs meant.

Soon, the British would, in 1900, introduce hut tax. It then dawned on the natives what the Arabs meant.

In past posts, I have stated than the name Kavirondo was coined by waswahili accompanying caravans into the interior. They described the common habit of the Luo people squatting on a lowly stool as “kukaa virondo”. Thus the Luo were described as “wale wakaa virondo”.

Wrote Oginga, somewhat corroborating accounts about the origin of the word “Kavirondo”:

“Early visitors took over the name Kavirondo which the Arab caravans had once used and gave the same name to all the peoples living in Nyanza, though they comprise totally distinct groups...”

“Early visitors took over the name Kavirondo which the Arab caravans had once used and gave the same name to all the peoples living in Nyanza, though they comprise totally distinct groups...”

Indeed, British administrators, who considered the Abaluhya and Luo to be one and the same people, had maps showing Nyanza and parts of western province as Kavirondo.

We also know that pioneer Nyanza missionaries, who were supported immensely in their work by Nabongo Mumia, Paramount Chief of the Abaluhya, referred to the Luo as “Kavirondo”.

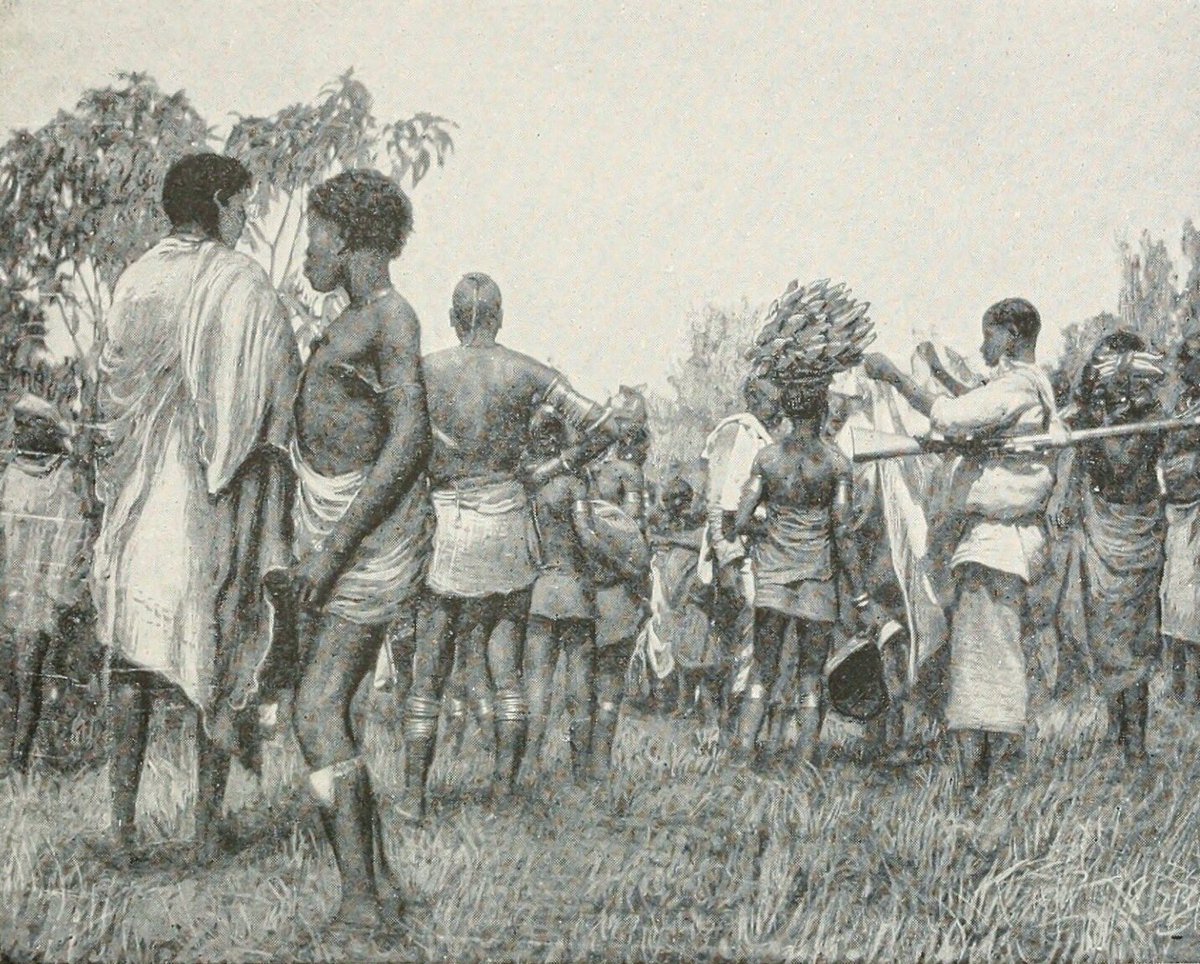

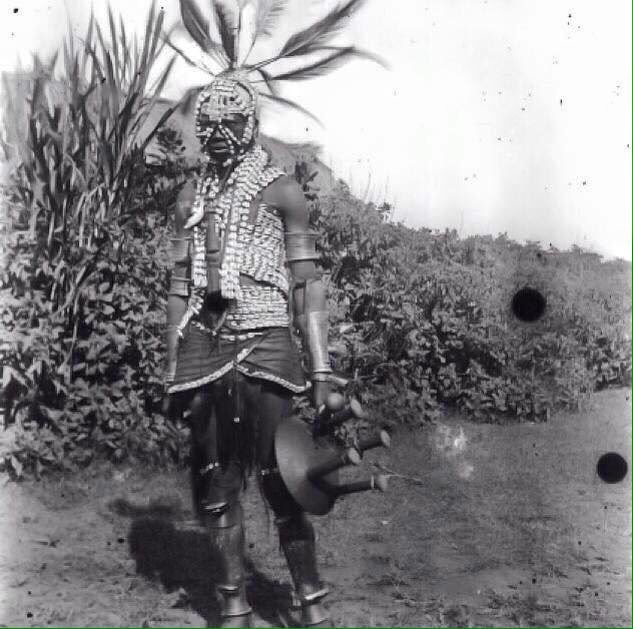

Young men were conscripted to serve under chiefs. In open fields, they were taught, to much amusement of locals, saluting and marching drills.

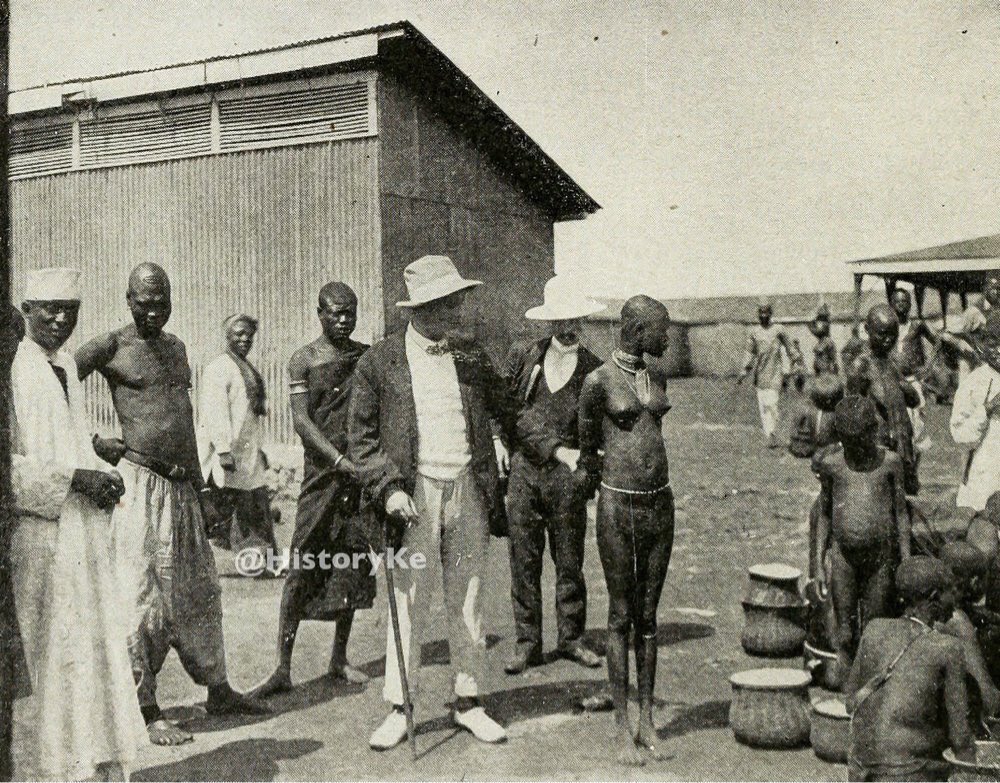

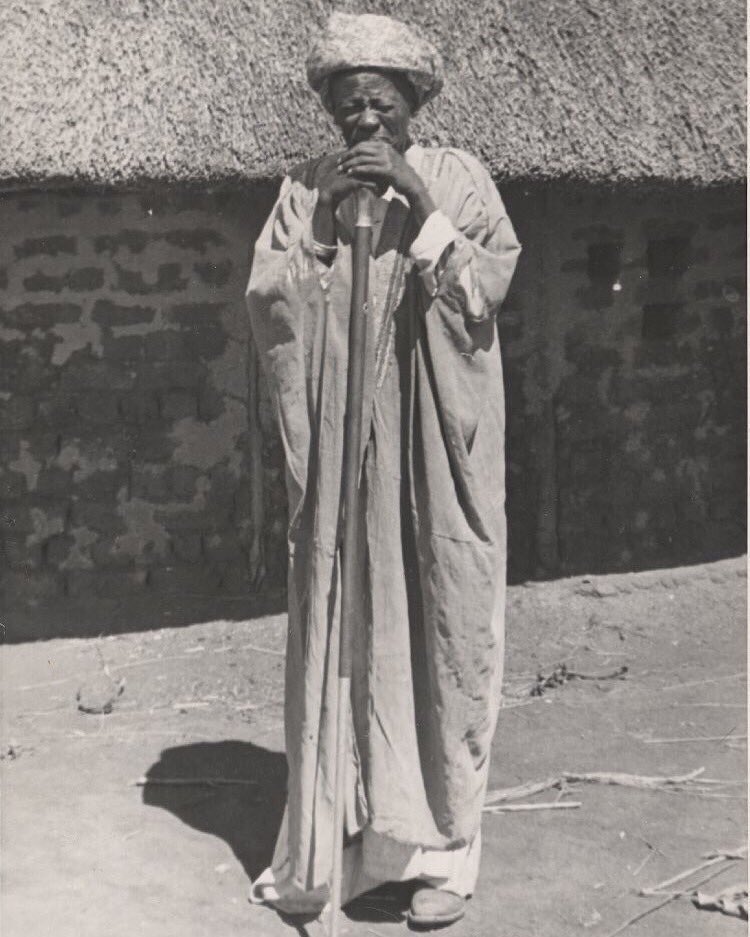

There was uproar when the colonial administrators proclaimed Mumia (pictured), one of whose bodyguards was Oginga’s father, Paramount Chief of all Nyanza.

Elders in Nyanza refused to recognize Mumia as their leader.

Elders in Nyanza refused to recognize Mumia as their leader.

Chiefs from Uyoma were most vocal in their opposition. Native askaris had to be sent to pacify them. It is not clear if Mumia was Paramount Chief of Nyanza till death (there was a PC). For when he died in 1949, he received something akin to a state burial, with military honours.

In those days, the office of Colonial Chief was considered prestigious. And at times elders used cunning ways to endear themselves to British administrators so they could land administrative appointments.

One of these was Jasakwa, who hailed from Sakwa. For some time, he served British interests in Kano, where he also learnt some Swahili.

When the Brits wanted to extend their administration to Sakwa, they sent Jasakwa the interpreter ahead to “clear the way” for them.

When the Brits wanted to extend their administration to Sakwa, they sent Jasakwa the interpreter ahead to “clear the way” for them.

“New people are coming - the white people”, he told Sakwa elders.

“They have dangerous weapons so don’t fight them. Instead, make a treaty with them”.

“They have dangerous weapons so don’t fight them. Instead, make a treaty with them”.

According to Oginga, Jasakwa wasn’t believed by the elders, who nevertheless sent him back with gifts to give to his white masters.

But Jasakwa had a clever plan for himself. This is what he said when he met his British employers:

But Jasakwa had a clever plan for himself. This is what he said when he met his British employers:

“The Chief says he cannot meet with you. He is the leader and it is not his duty, he says, to welcome strangers. I myself bring you these gifts...”

Impressed by Jasakwa’s hospitality, the British appointed him chief of Sakwa. Only Kenyans would understand, tongue-in-cheek, that this was an early “handshake”

The people of Sakwa would soon afterwards be up in arms.

The people of Sakwa would soon afterwards be up in arms.

“We have our Chief. The man you appointed serves as a messenger and interpreter for our chief...”

But the British would have none of that.

I am not sure what happened to Jasakwa. And even Oginga, who wrote briefly about him, doesn’t tell us.

But the British would have none of that.

I am not sure what happened to Jasakwa. And even Oginga, who wrote briefly about him, doesn’t tell us.

But maybe one of Jasakwa’s descendants is reading this.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh