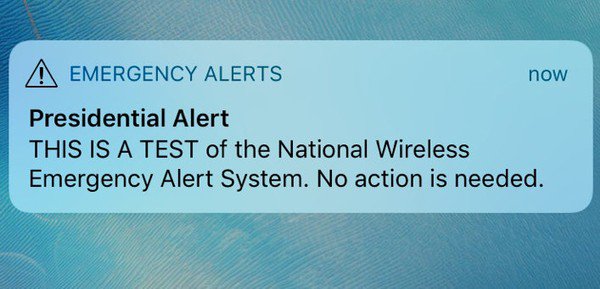

If you’re in the US at the moment, you almost certainly got one of these yesterday. There’s been a lot of confusion about what it is (and what it is not). Let me tell you more about emergency alerts using computer science, history, and of course, Batman. #news 1/

Emergency alerts were deployed in the US in 1951 via the Control of Electromagnetic Radiation (CONELRAD) system. Fearing a nuclear attack during the Cold War, radios could be tuned to 2 AM frequencies (see triangles) to receive civil defense information 2/ radiomuseum.org/forumdata/user…

As the threat of attack decreased, the desire to expand such a system for use in local emergency coordination allowed for the better known Emergency Broadcast System (EBS) to replace CONELRAD in 1963. You’ve heard EAS on your radios and TVs. 3/

Citing the need to improve automation and to expand the range of devices

capable of receiving emergency messages, the Emergency Alert

System (EAS) replaced the EBS in 1996. 4/

capable of receiving emergency messages, the Emergency Alert

System (EAS) replaced the EBS in 1996. 4/

EAS, managed by FEMA, the FCC and the National Weather Service, unified messaging formats using the Special Area Message Encoding (SAME) protocol. The goal of this protocol was to encourage automation and enable the entire population to be alerted in under 10 minutes. 5/

But EAS didn’t reach everyone, because not everyone was near a radio or TV at all times. But they were near their cell phone. Tragedies like the Virginia Tech shooting made it clear that old methods for alerting didn’t meet modern needs. 6/

The Virginia Tech shooting plays a significant role in what happens next. US universities purchased SMS mass messaging systems to send out alerts to students during an emergency. If you went to college in the 2000s, your school had one of these 7/

The problem? When disaster struck, 50k-100k unicast messages were dumped into the network, and caused accidental DoS attacks. Provider systems often simply dumped these messages because they looked like an attack. Those that got through took hours: sfu.ca/sfualerts/apri… 8/

I worked with providers in 2008-2009 to push Congress on making changes to the Warning, Alert and Response Network (WARN) Act, which mandated that alert messages be sent to phones. My work pointed to situations like the above. 9/

Ultimately, this partnership worked, and Congress granted an extension so that “Cell Broadcast” could be deployed. Instead of unicasting messages to people who had to sign up to receive them, anyone near a tower could efficiently received an alert 10/

Cell broadcast is why your phone makes noise during an Amber or Silver Alert. Next time your phone makes noise like crazy, feel free to allocate a tiny sliver of the blame to me 11/

(As an aside, I submitted an academic paper on this work to SIGCOMM at the time, only to be told that the work was “not relevant”. It changed law in the US and 10 years later, it’s partially responsible for annoying you. Take that, Reviewer 2!) 12/ ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/61883…

Presidential Alerts are just the most recent extension of the national alert system. They have nothing to do with the current president, and these efforts were started long before he was in office. It’s all part of the Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) standards. 13/

What are these alerts not? Well, they’re not this tweet: 14/

https://twitter.com/officialmcafee/status/1047585232831041536

That’s not how this works. This is a broadcast standard. It’s about receiving information efficiently. There’s a nice write-up about Cell Broadcast on Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cell_Broa… 15/

“But Professor Traynor, I saw ‘The Dark Knight’ and Batman…” (told you we’d get here). Let me stop you right there. We can all agree that Christopher Nolan’s Batman is the greatest, but he’s completely wrong about cellular systems 16/

In that movie, Batman activates all phones in the city and uses them to “turn every phone in Gotham into a microphone”. That kind of capacity doesn’t exist in real networks. Proof? Ever get a busy signal? I rest my case. 17/

So, to wrap this up, the Presidential Alert you likely received yesterday has nothing to do with the current president, and is instead part of a long progression of national alert systems started during the Cold War. It’s also not being used to spy on you 18/

You can’t shut it off, just like you can’t shut off emergency notifications on your TV or radio. You can turn your device off, which is probably a good thing for everyone to do on occasion anyhow 19/19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh