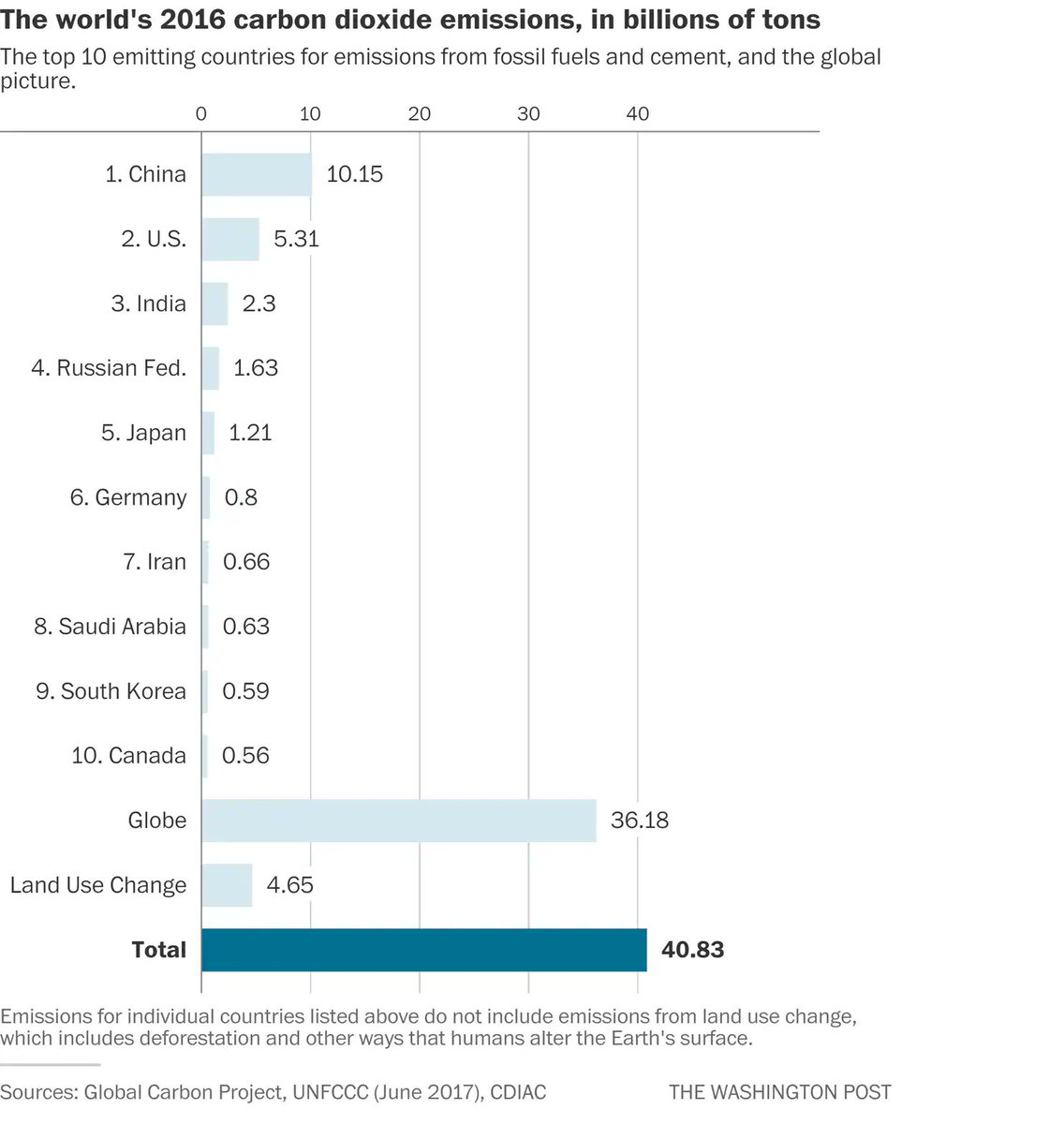

1. These are today's emissions and top emitters. We included this graphic for a reason. #SR15 washingtonpost.com/energy-environ…

2. As we put it, in order to hold warming to 1.5C, "overall reductions in emissions in the next decade would probably need to be more than 1 billion tons per year, larger than the current emissions of all but a few of the very largest emitting countries." @brady_dennis

3. So, most of these countries. We'd have to cut emissions every year by more than most of these countries emit annually. That is the scale of what is being talked about.

4. Some other key details about the huge, "unprecedented" lift that is being proposed if the world is somehow to hold warming to 1.5 C, either entirely, or with only a minor overshoot.

5. As we note in the piece, according to @iea, only 4 percent of road transport is now powered by renewable fuels. And only slow change is expected in this sector. Somehow, the pace of change here would have to be hugely sped up in just a decade iea.org/media/publicat…

6. The @IPCC_CH also says there has to be a big change in how land is used -- devoting vast areas to carbon-storing forests and crops for energy (BECCS). “Such large transitions pose profound challenges for sustainable management of the various demands on land," it says.

7. One could go on. But clearly ,the question is how this change without "historic precedent" can happen.

8. There are going to be a lot of takes on this. A lot. In our story, @Peters_Glen offered one of them: "Even if it is technically possible, without aligning the technical, political and social aspects of feasibility, it is not going to happen." /end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh