European civilization is built on ham and cheese, which allowed protein to be stored throughout the icy winters.

Without this, urban societies in most of central Europe would simply not have been possible.

This is also why we have hardback books. Here's why. 1/

Without this, urban societies in most of central Europe would simply not have been possible.

This is also why we have hardback books. Here's why. 1/

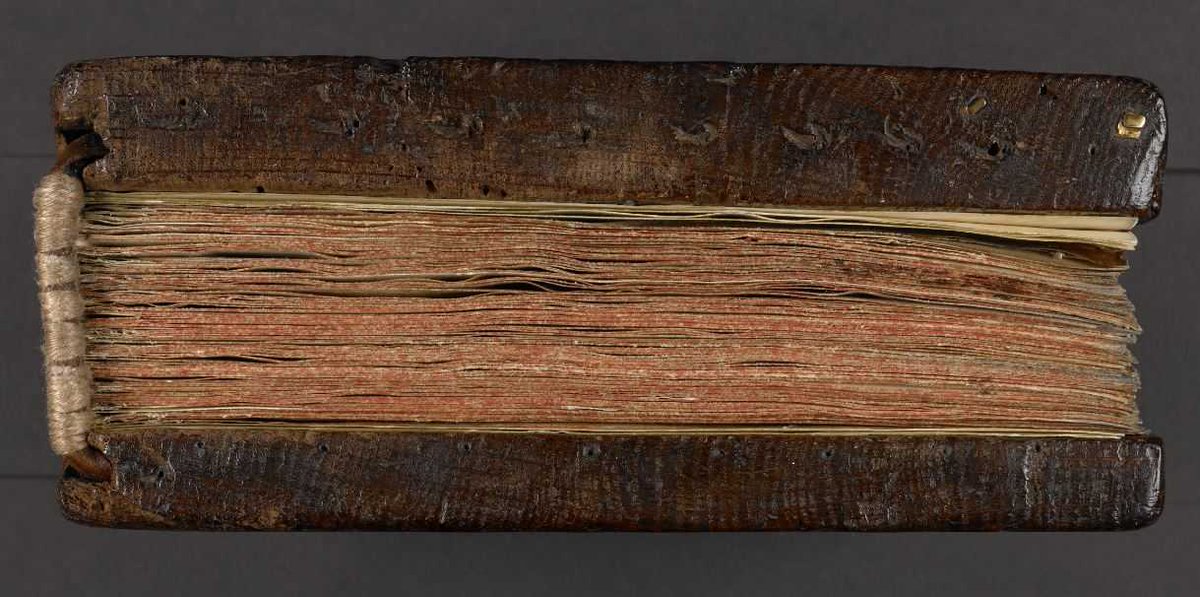

Cheese meant female sheep & cows were usually more valuable than male ones which were accordingly slaughtered young as they were not worth feeding through the winter. The skins of these young animals was used to make vellum, giving us the basic material of the European book. 2/

Vellum tends to buckle & ripple, it doesn't lie absolutely flat like paper. So it was bound between heavy wooden boards to keep it flat - this is the origin of the hardback book, a book format - expensive, hard to make, & prone to damage - almost never seen outside Europe. 3/

Cheese 🧀 is one of the 5 things the Western book as we know it depends on. The other four are snails 🐌, Jesus ✝️, underwear 🩲 and spectacles 👓. If even one of these things was absent, the book you hold in your hand today would look completely different. I'll explain why. 5/

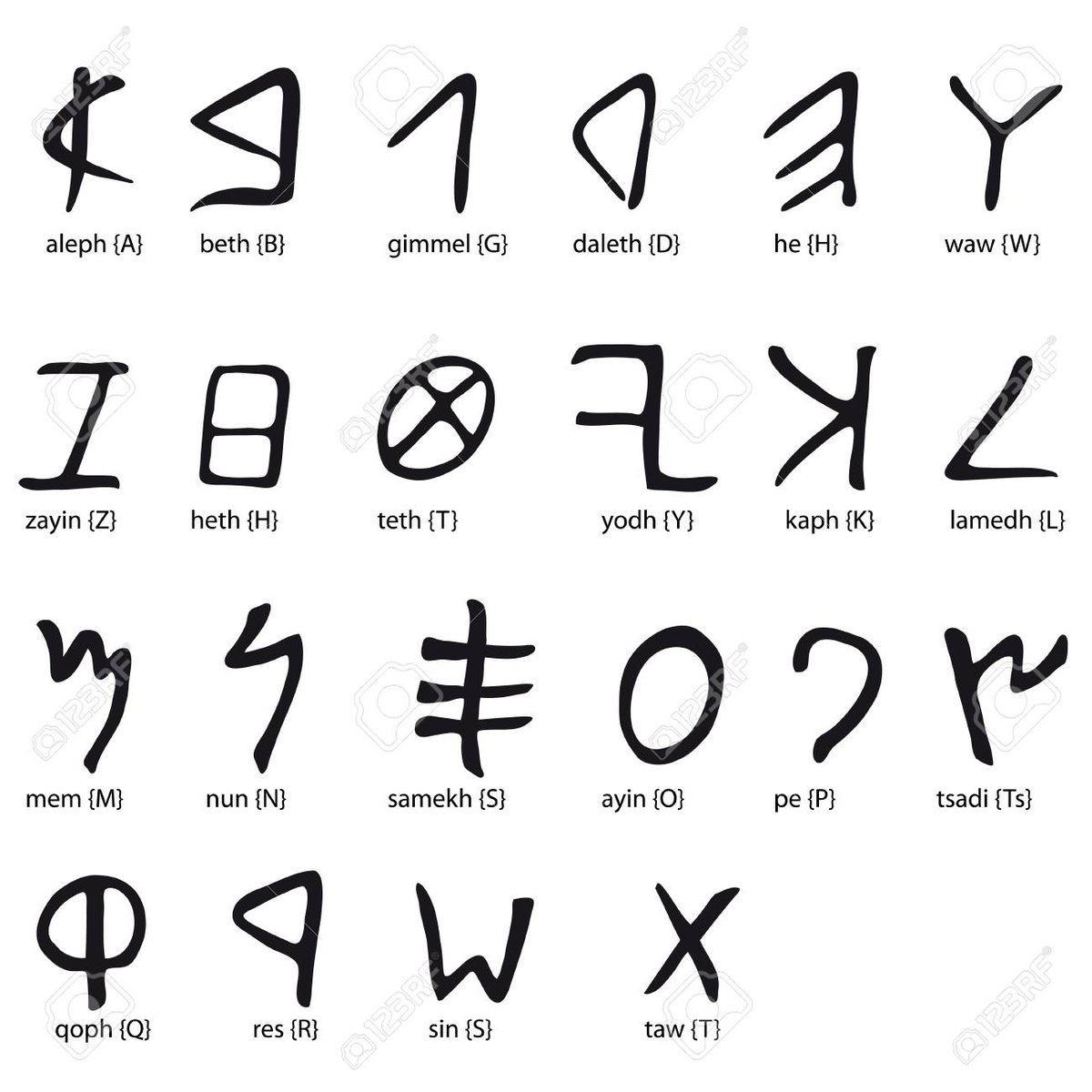

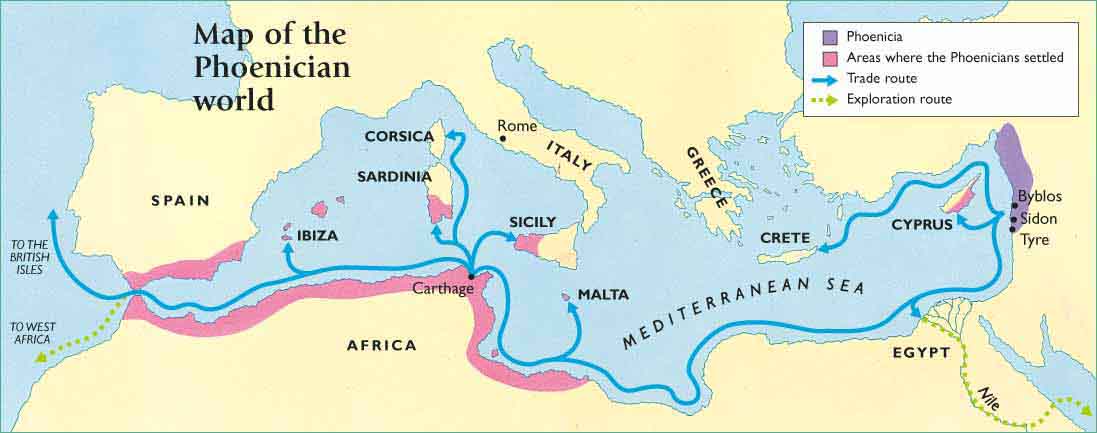

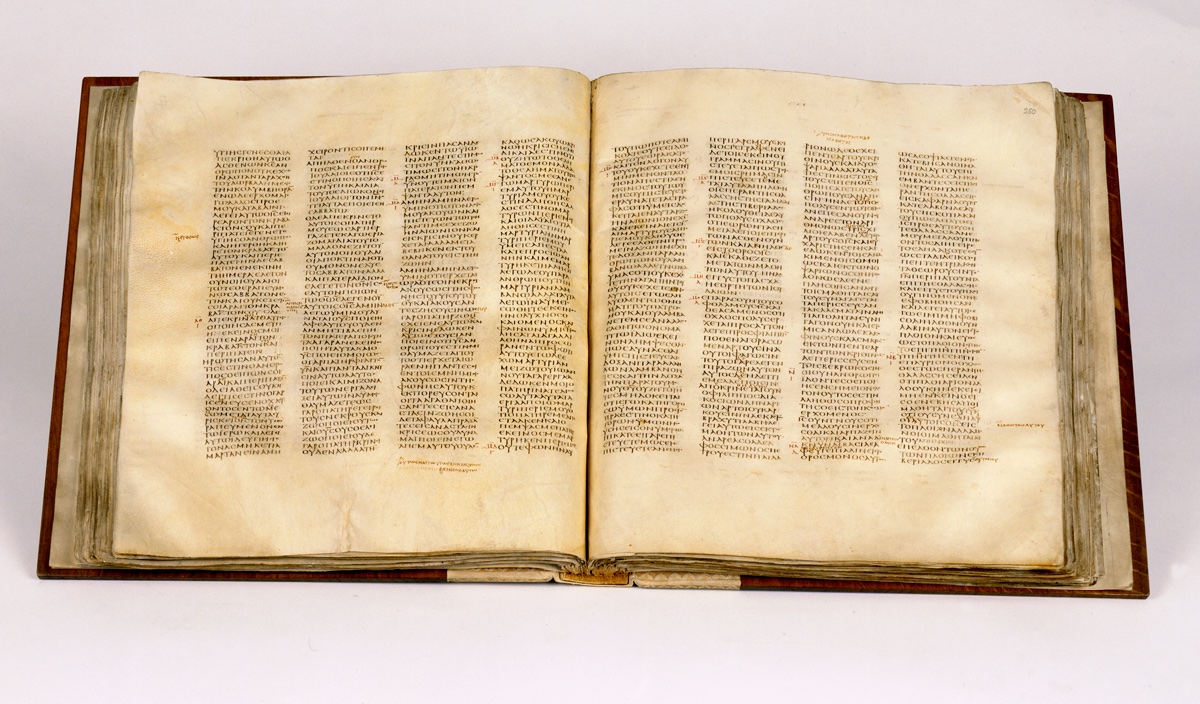

There are -surprisingly - only four definite independent originations of writing, of which only two survive today, and there’s only ONE alphabet - the one developed by the Phoenicians, from which all the others, including our own, derive. 6/

A particular characteristic of an alphabet (as opposed to a syllabary) is its ability to adapt to represent entirely different sounds and languages. This was likely important to the Phoenicians, whose civilization was spread out over 1000s of km of Mediterranean coastline. 7/

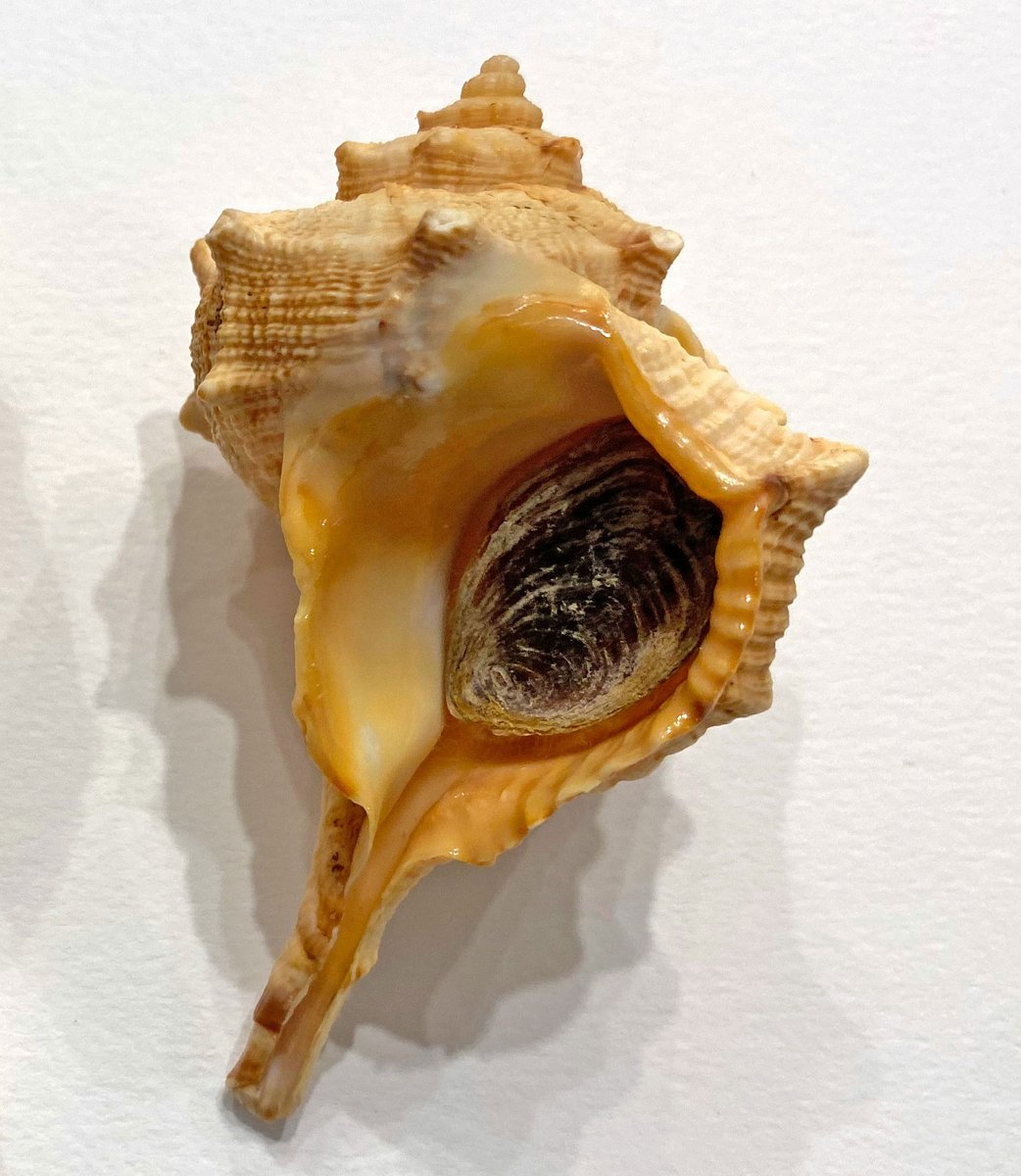

The Phoenician civilization extended over these vast coastal distances at least partly because of the economic importance of their dye-extraction industry. A sea snail - Bolinus Brandaris, the dye-murex - provided the sought after purple dye for which they were famous. 8/

So no sea snails, no widespread Phoenician civilization, and no widespread use of the Phoenician alphabet, from which our ABC today derives. No alphabet would mean no widespread use of movable type (as in Asia, where it was tried, but proved inferior to woodblock printing). 9/

In short: the letters in the book you are reading today, and the near universal adoption of movable type printing in the West, both depend on these sea-snails. 10/

So that's why our books depend on cheese and snails. What about Jesus, underwear and spectacles? 11/

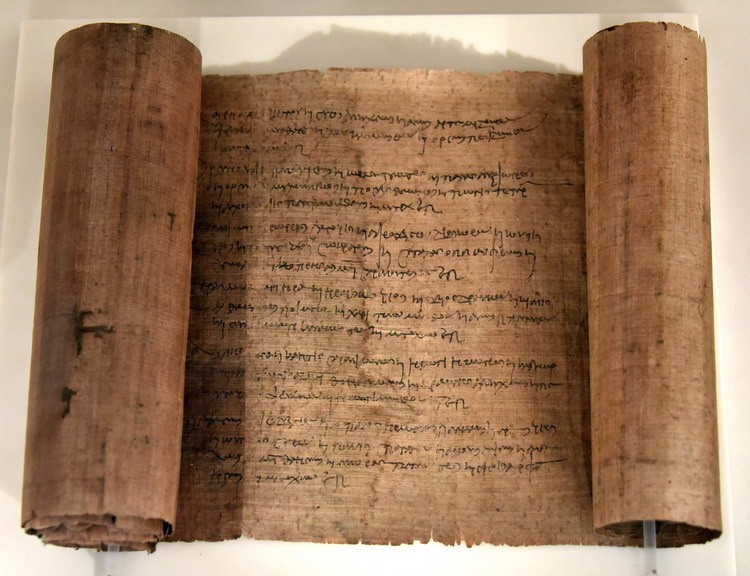

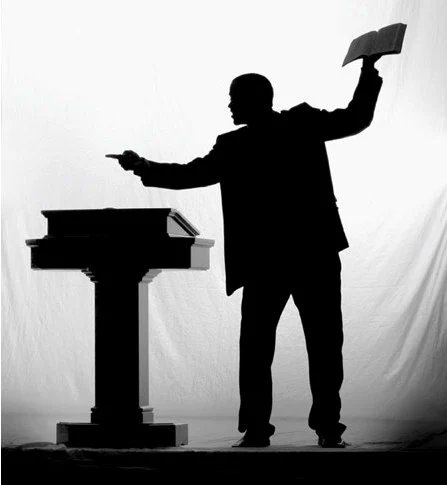

In antiquity, the book in Europe and the Near East was written on tablets or on scrolls. The adoption of the codex form in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD coincided with the early spread of Christianity, and is vastly more prevalent in early Christian texts than in secular ones. 12/

The reasons for this are not clear & all the hypotheses are disputed to some degree. One idea is that Christianity was spread by proselytising preachers who were able to hold their codex gospels in one hand (a scroll would require two), leaving the other hand free to gesture. 13/

Whatever the reason though, there’s no disputing that the adoption of the codex form and its near total replacement of the scroll format in Europe and the Near East, coincided with and was intimately tied up with the early spread of Christianity. 14/

So that's cheese, snails and Jesus explained. Why underwear and spectacles? 15/

Without the availability of paper, there would have been no printing revolution in the 15th century.

Without underwear, there would have been no widespread availability of paper.

The book in Europe developed as it did, because of underwear. Here’s why. 16/

Without underwear, there would have been no widespread availability of paper.

The book in Europe developed as it did, because of underwear. Here’s why. 16/

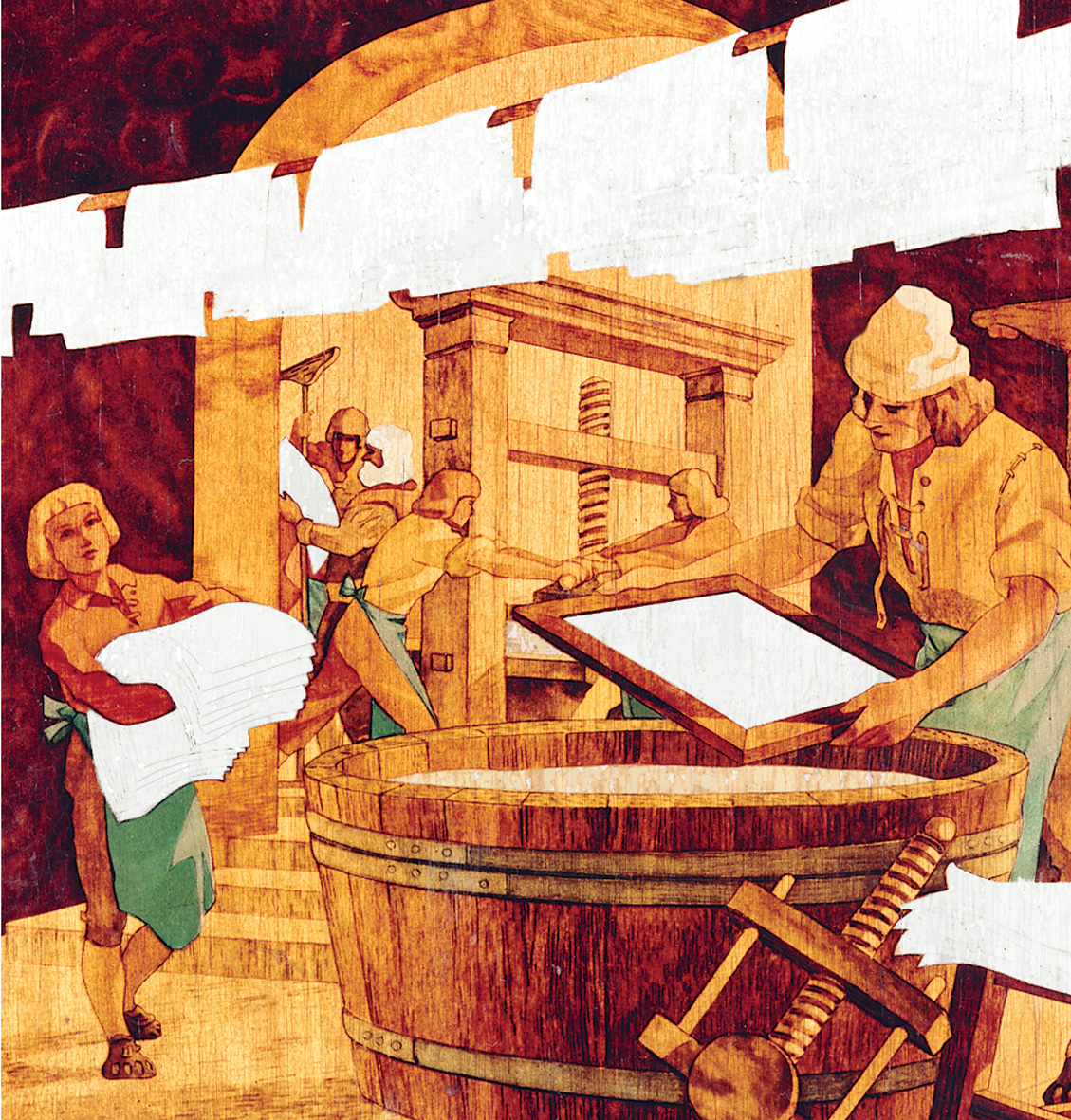

Traditional papermaking in Asia uses the inner bark fibers of plants. Papermaking in Europe developed on fundamentally different lines because of the absence in Europe of an indigenous pulp source such as the paper mullberry [Broussonetia papyrifera] widespread in Asia. 17/

It was not until the early 19th century that paper production from wood pulp became technically and commercially viable in Europe. Until then paper in Europe was made from rags. But what rags? 18/

Rags for papermaking needed to be generally uncolored, and made from linen, hemp or cotton. Most clothing was made from wool, and wool fabrics were not usable at all for rag paper production. So what was the source of uncolored linen or cotton rags? Primarily underwear. 19/

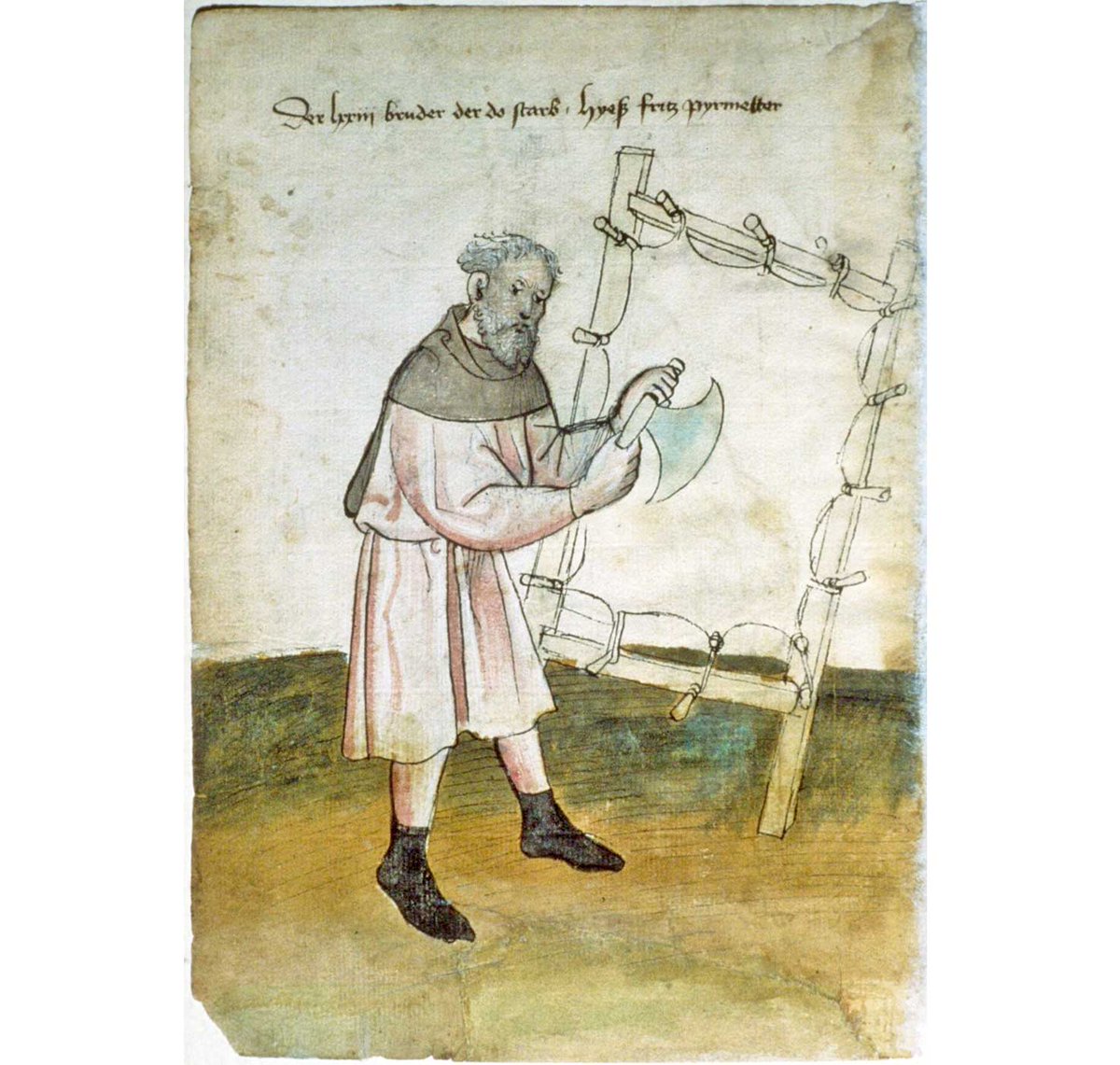

While loincloths were worn, by slaves particularly, in Roman antiquity, it was only from the Middle Ages onwards that the wearing of underwear became widespread in all classes - specifically linen braies or drawers for men, and linen shifts or chemises for women. 20/

Key to this was the availability of affordable linen, which, unlike wool, was cool & comfortable on the skin. The breakthrough was the invention in the 14th cent. of the spinning wheel for flax, which made manual spinning obsolete, and resulted in drastically cheaper linen. 21/

Linen underwear - uncolored and washed often (and thus prone to wearing out) - was an ideal source for rags for papermaking. And the new availability of low-cost linen due to the spinning wheel coincided exactly with the hugely increased demand for paper in the 15th century. 22/

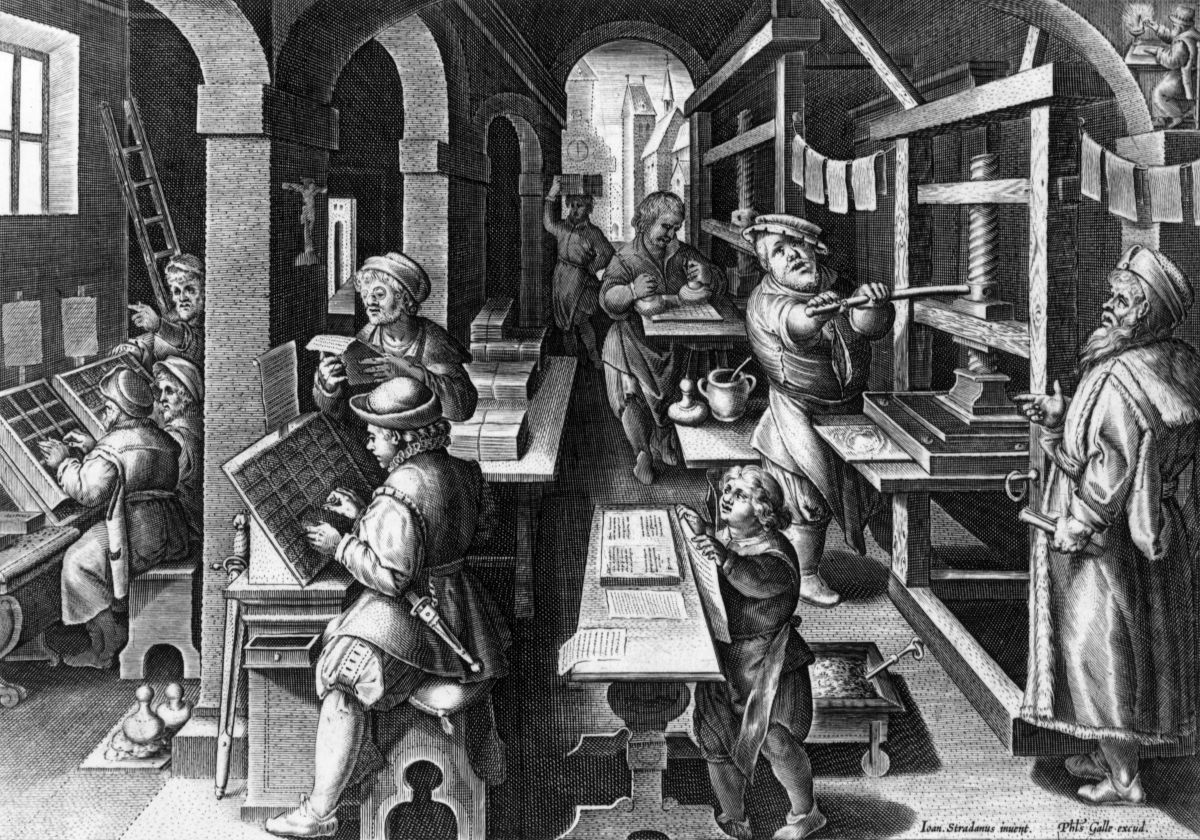

Printing was only economically viable because of the availability of paper. It would never have developed in the 15th and 16th centuries into the vast Europe-wide industry it did if vellum - hugely expensive and difficult to work with - had been the only available option. 23/

Paper production was viable because of the availability of linen rags. And linen rags existed - not exclusively, but certainly above all - because people wore linen underwear.

No underwear - no rags, no paper, no printing, and perhaps no book as we know it today. 24/

No underwear - no rags, no paper, no printing, and perhaps no book as we know it today. 24/

We've now covered cheese, snails, Jesus and underwear. Spectacles next! 25/

🧀 + 🐌 + ✝️ + 🩲 + 👓 = 📖

🧀 + 🐌 + ✝️ + 🩲 + 👓 = 📖

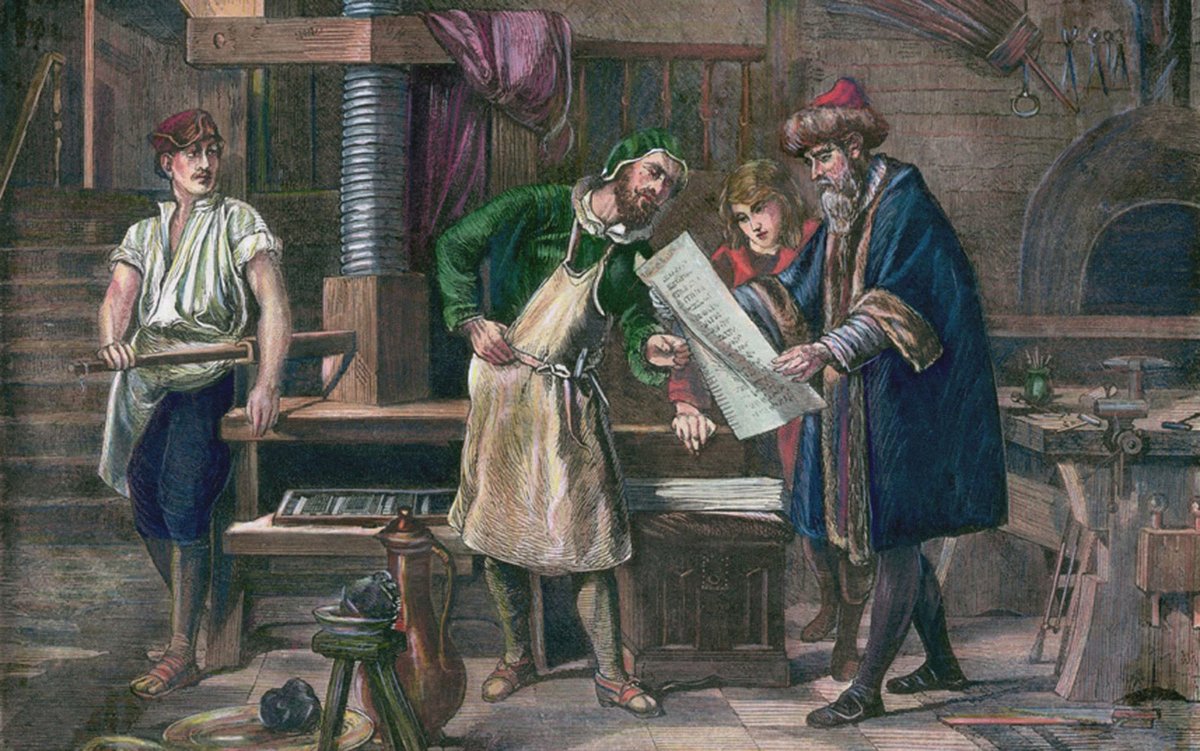

The invention of spectacles made Gutenberg possible.

Gutenberg’s invention - and the spread of European printing that followed it - was not just a technological revolution, but a commercial one as well. Spectacles enabled it. Here's why. 26/

Gutenberg’s invention - and the spread of European printing that followed it - was not just a technological revolution, but a commercial one as well. Spectacles enabled it. Here's why. 26/

Manuscripts were - primarily - produced on a one-off basis as needed. But printing involved producing and financing an entire edition - 100's or 1000's of copies - upfront. This necessitated finding many buyers rapidly, so that the printer could recover his capital outlay. 27/

From the 13th century, the customer-base for manuscripts had expanded beyond the traditional monastic, clerical & courtly circles to students, scholars and lay-people - a process which had resulted in a streamlining of production and the organization of scribal workshops. 28/

All this resulted in falling production costs. The advent of printing not only accelerated this out of all recognition, but made it absolutely imperative to sell books to the widest market possible - printing needed customers, and lots of them, to be commercially viable. 29/

Then and now, a key book-buying demographic was men - and women - in their 40s and upwards. These people were disproportionately likely to have the leisure time to read and the all-important wealth or disposable income needed to actually buy books. 30/

The problem though - then and now - was that most people over 40 can no longer read comfortably or even at all, due to the naturally occurring presbyopia - age-related long-sightedness - that inevitably comes with the onset of middle-age.... 31/

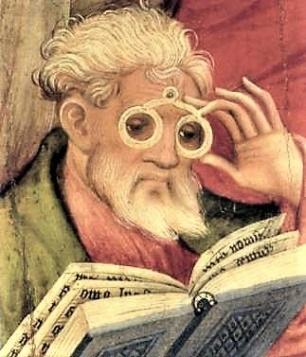

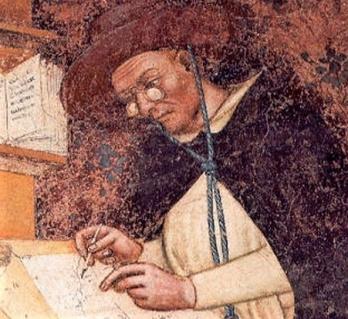

Most historians believe that the first form of eyeglasses was produced in Italy by craftsmen in Pisa (or Venice) around 1285-1289. These lenses for reading were shaped like two small magnifying glasses and set into metal or leather mountings, balanced on the bridge of nose. 32/

The manufacture & use of eyeglasses spread rapidly across Europe from the end of the 13th century onwards. By 1301, there were guild regulations in Venice governing the sale of eyeglasses. By the late fourteenth century they were common objects, widely available everywhere. 33/

So when Gutenberg set up his press in the 1450s, his customer base - and that of the printers who followed him in subsequent decades - included the all important 40+ demographic, who were, thanks to eyeglasses, able to comfortably read his books. 34/

Without spectacles, Gutenberg would have had significantly fewer customers - and given that the economics of early printing were very finely balanced between success and failure, perhaps too few to make his new process commercially viable. 35/

It's worth reading Vincent Ilardi's excellent "Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes" on the early history of reading glasses - it's an interesting subject with all sorts of ramifications in other spheres, quite apart from book production. 36/

books.google.fr/books?id=peIL7…

books.google.fr/books?id=peIL7…

So - finally - after this meandering thread of 36 tweets, we see that 🧀 + 🐌 + ✝️ + 🩲 + 👓 = 📖

QED!

QED!

Some hard-to-please curmudgeons [note to self: replace with "valued followers" before tweeting] have complained that the section above on sea-snails is insufficiently clear. So let me elaborate on these connections in a little more detail. 38/

I'm not saying that we would not have a writing system without the Phoenicians (or the dye murex). Of course we would have. What I'm saying is:

1. Without the dye murex, Phoenician civilization would likely have developed differently, both temporally and spatially. 39/

1. Without the dye murex, Phoenician civilization would likely have developed differently, both temporally and spatially. 39/

2. As a result, it’s entirely possible - perhaps even likely - that the Greeks would have developed or adopted another writing system, not specifically the one the Phoenicians used. Remember that almost all European alphabets in turn derive from the Greek one. 40/

3. Considered globally, an alphabet is an extremely unusual form of writing system. Most writing systems - the Chinese one is a good example - are syllabaries, combined with logograms. This is arguably the “natural” form of writing systems. 41/

In the 19th century, when missionaries created writing systems de novo for indigenous peoples in the Americas or Asia, they almost always settled on syllabaries (even though they themselves wrote with an alphabet). A syllabary is simply much easier and more natural to learn. 42/

4. A characteristic of all syllabic writing systems is that they require far more graphemes - ie symbols - than does an alphabet. Where this is combined with logograms as well, this number can be very high - for example, potentially 50 000+ for Chinese and Japanese. 43/

5. The unstoppable success of movable type printing in the West from the mid 15th century is intimately tied up with the small number of graphemes in our unique and unusual writing system: the alphabet. 44/

The complexity, expense, and overall difficulty of casting and setting type for many hundreds or thousands of different characters, rather than the few dozen we have, can easily be imagined. 45/

6. This is the primary (although not only) reason that movable type printing - although developed in China and Korea centuries before the West (and used in Japan in the late 16th and 17th century) - never caught on to the same extent as in Europe. 46/

In all three countries it was largely abandoned with an across-the-board reversion to woodblock printing. China, Japan & Korea, having abandoned movable type continued to use woodblock printing until the advent of technologies like lithography & stereotyping in the 19th cent. 47/

So in short, a line can be drawn from the dye-murex, via the Phoenician alphabet, to the unique success of movable type printing in the West, a success not duplicated in a similar way anywhere else, & never with the non-alphabetic scripts that are the norm in Asia especially. 48/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh