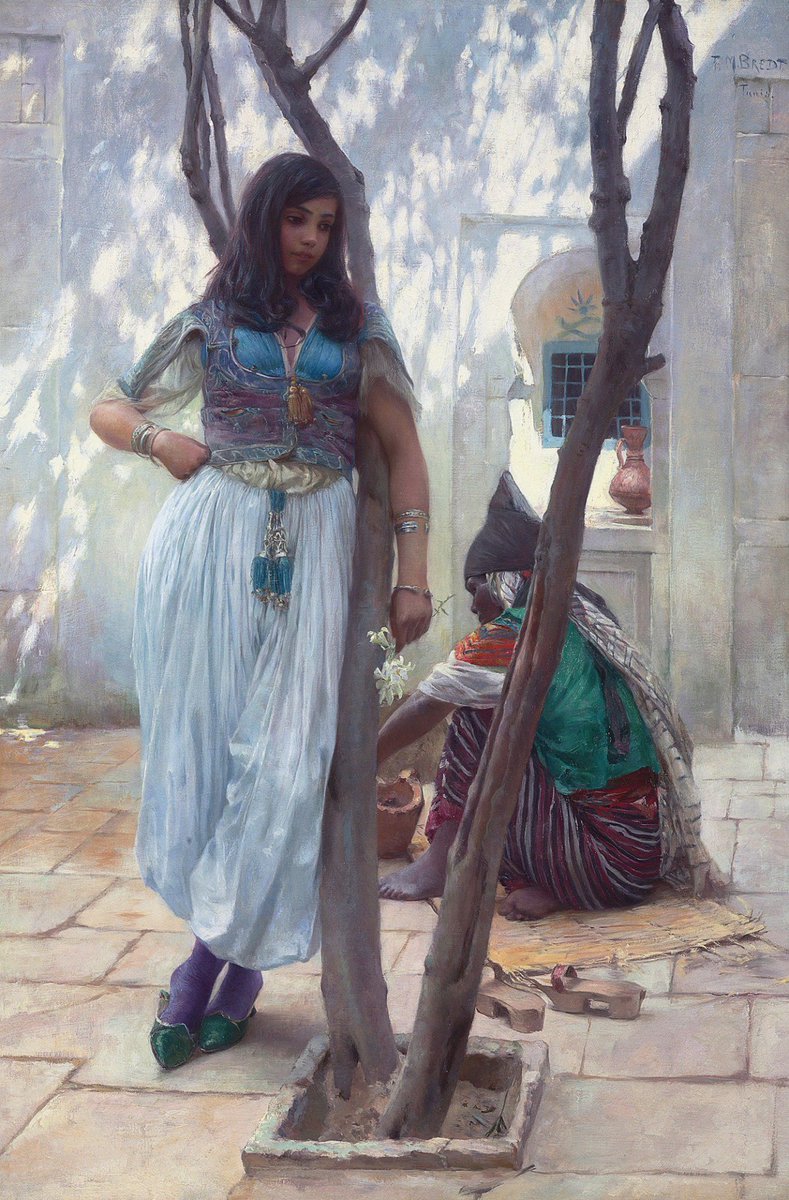

#1800sWeek!

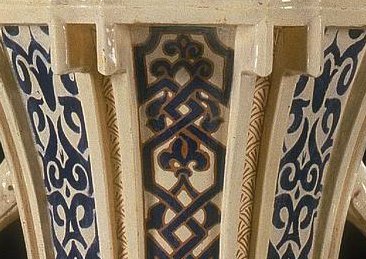

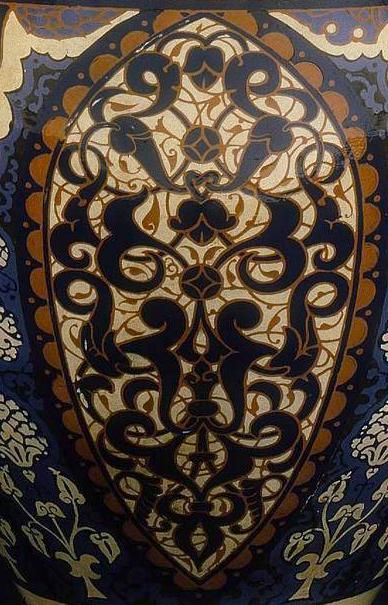

Okay! So! Works like these fall under the category of "Orientalism". They do not accurately represent any culture or people, and were created as sort of Western fantasies of "The Middle East" and/or "Asia". The history of the term and the concept are complicated.

Okay! So! Works like these fall under the category of "Orientalism". They do not accurately represent any culture or people, and were created as sort of Western fantasies of "The Middle East" and/or "Asia". The history of the term and the concept are complicated.

In 1978, Edward Said redefined the term Orientalism to describe a pervasive academic & artistic Western tradition of prejudiced interpretations of the Eastern world, shaped by the cultural attitudes of European imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientali…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh