1. At the risk of trying to bring some nuance to Twitter, what follows is a #thread on U.S. law vis-a-vis the war powers, and why the legality of the #SyriaStrikes as a matter of U.S. law (to say nothing of int'l law) is both far from certain and revealing of far deeper problems:

2. Let's start from first principles. For uses of military force to be lawful as a matter of U.S. domestic law, the authority to use such force must stem either from an Act of Congress or from the President's powers under Article II of the Constitution.

3. As the government has already implicitly conceded, no statute authorized these strikes.

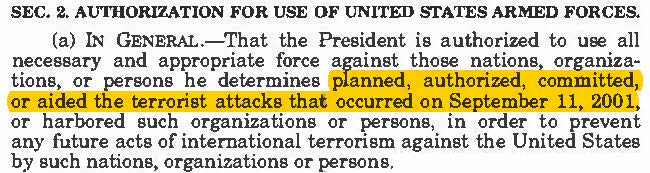

Although both the Obama and Trump administrations have relied upon the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (#AUMF) to use force _in_ Syria, those strikes were against #ISIS.

Although both the Obama and Trump administrations have relied upon the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (#AUMF) to use force _in_ Syria, those strikes were against #ISIS.

4. There's serious debate (& ongoing litigation) over whether ISIS is covered by the AUMF; contra the pictured statutory text, ISIS had nothing at all to do with the 9/11 attacks.

But there's no argument whatsoever that the 2001 AUMF authorizes the use of force against _Assad_.

But there's no argument whatsoever that the 2001 AUMF authorizes the use of force against _Assad_.

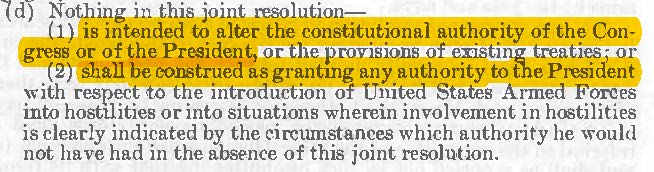

5. A lot of commentators have pointed instead to the War Powers Resolution of 1973, a framework statute Congress enacted during Vietnam in an attempt to rein in unilateral presidential warmaking.

But the WPR itself specifies that it can't be read that way—as authorizing force:

But the WPR itself specifies that it can't be read that way—as authorizing force:

6. Instead, the most pro-Executive Branch reading of the WPR is that it creates a 60-day window in which unilateral uses of force are not _prohibited_ (at the end of the 60 days, the statute mandates withdrawal of the relevant troops absent intervening congressional action).

7. But that's not the same thing as authorization. So the question reduces to whether the President can rely on his unilateral authority under Article II of the U.S. Constitution.

There's general consensus that Article II authorizes the President to use force in "self defense."

There's general consensus that Article II authorizes the President to use force in "self defense."

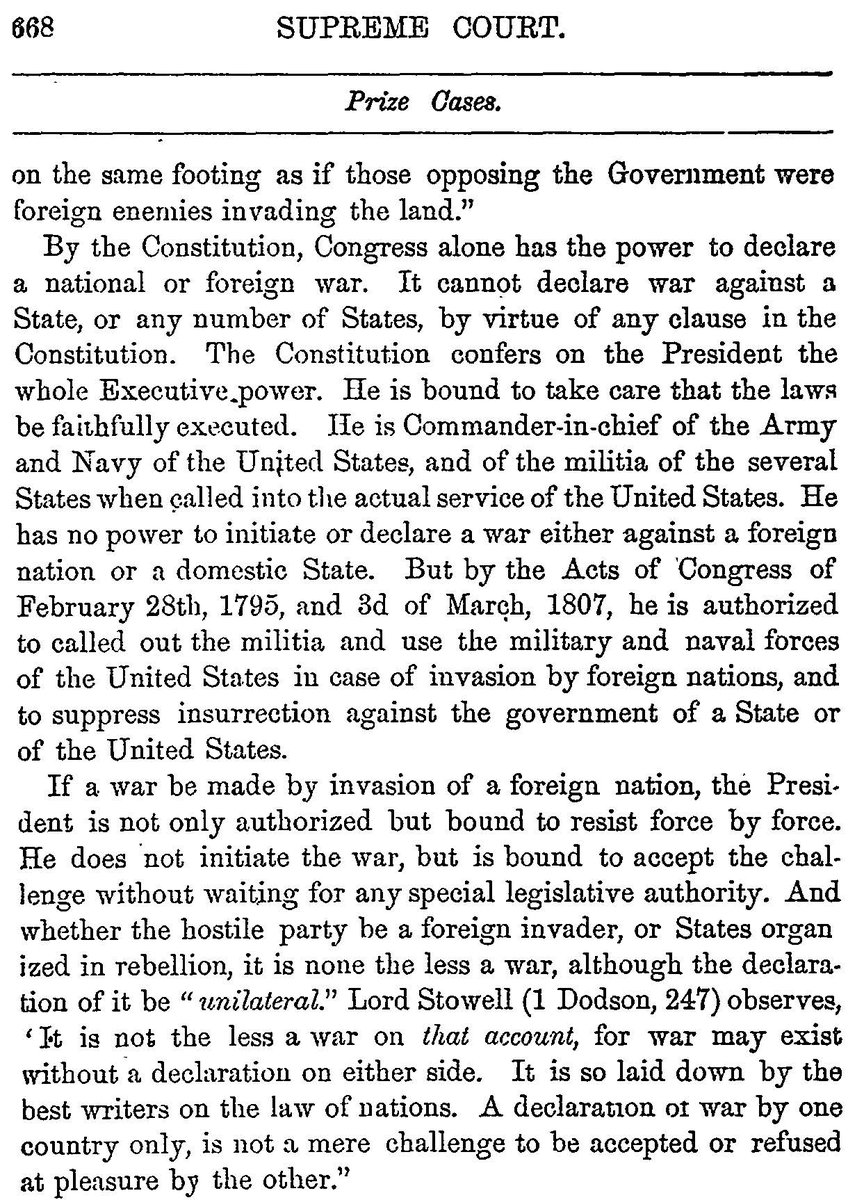

8. Here's perhaps the most on-point discussion by #SCOTUS—in its important, but often overlooked, 1863 decision known as the "Prize Cases":

law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/t…

law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/t…

9. Wherever the line is between offense and defense, it's hard to see how strikes like last night's are on the "defense" side, given lack of imminent threat to the U.S.

Instead, they're defended under a broader theory—that Article II "self defense" includes "national interests."

Instead, they're defended under a broader theory—that Article II "self defense" includes "national interests."

10. It should go without saying that protecting "national interests" is far broader than "self defense."

It should also go without saying that the Prize Cases reasoning—that the President shouldn't have to wait for Congress to defend the country—doesn't apply to such a claim.

It should also go without saying that the Prize Cases reasoning—that the President shouldn't have to wait for Congress to defend the country—doesn't apply to such a claim.

11. The problem is that, so long as the uses of force are limited (thereby not running into the War Powers Resolution's time-based prohibition), there's no clear legal mechanism to push back against these kinds of Article II arguments.

Instead, the remedies here are political.

Instead, the remedies here are political.

12. But Congress has been remarkably unwilling, in the 45 years since the War Powers Resolution was enacted, to actually push back against these kinds of limited, unilateral uses of force—whether through spending cutoffs or other efforts to cabin them by statute.

13. That's been true when both Democrats & Republicans have been in control of Congress, and when both Democrats & Republicans have been in the White House. The issue here is a lack of institutional will—which has produced a drift in the perception, if not reality, of war powers.

14. So if the Q. is whether the #SyriaStrikes were legal as a matter of US law, the answer is "almost certainly not."

If the Q. is whether there's precedent for them anyway, the answer is "sort of."

And if the Q. is how do we _fix_ this, the answer, alas, is "Congress."

/end

If the Q. is whether there's precedent for them anyway, the answer is "sort of."

And if the Q. is how do we _fix_ this, the answer, alas, is "Congress."

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh