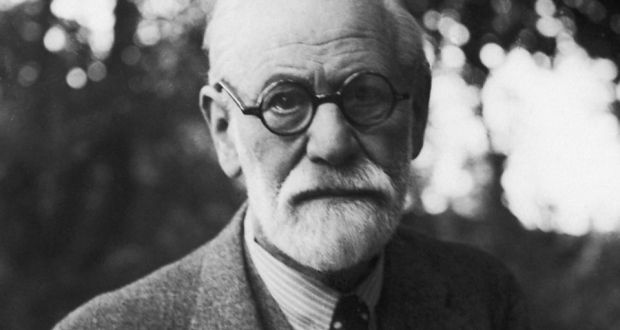

Sigmund Freud died #OnThisDay in 1939.

Freud was born to Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg, in the Austrian Empire (later Příbor, Czech Republic), the first of eight children. Both of his parents were from Galicia, in modern-day Ukraine.

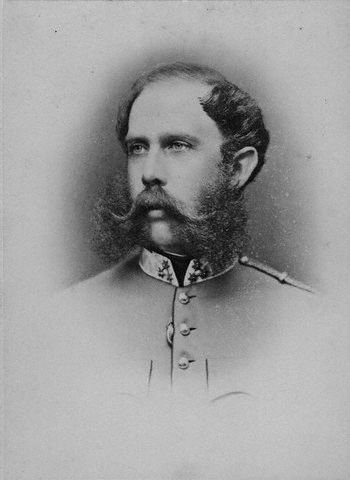

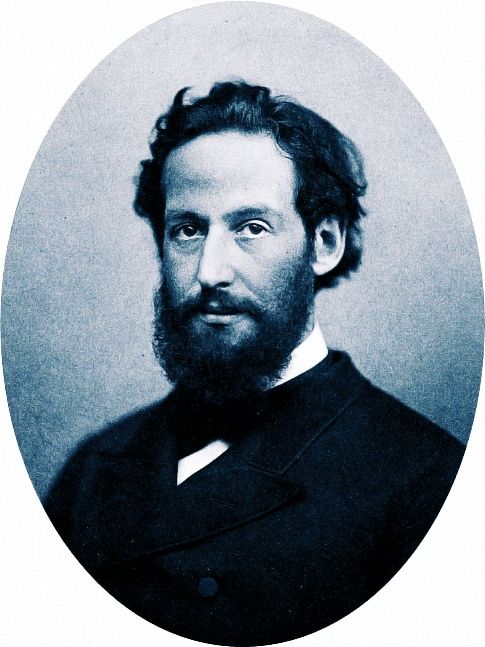

His father, Jakob Freud (1815–1896), a wool merchant, had two sons, Emanuel (1833–1914) and Philipp (1836–1911), by his first marriage.

Jakob's family were Hasidic Jews, and although Jakob himself had moved away from the tradition, he came to be known for his Torah study.

Jakob's family were Hasidic Jews, and although Jakob himself had moved away from the tradition, he came to be known for his Torah study.

He and Freud's mother, Amalia Nathansohn, who was 20 years younger and his third wife, were married on 29 July 1855.

They were struggling financially and living in a rented room, in a locksmith's house at Schlossergasse 117 when their son Sigmund was born.

They were struggling financially and living in a rented room, in a locksmith's house at Schlossergasse 117 when their son Sigmund was born.

In 1859, the Freud family left Freiberg. Freud's half-brothers emigrated to Manchester, England, parting him from the "inseparable" playmate of his early childhood, Emanuel's son, John.

Jakob Freud took his wife and two children (Freud's sister, Anna, was born in 1858; a brother, Julius born in 1857, had died in infancy) firstly to Leipzig and then in 1860 to Vienna where four sisters and a brother were born.

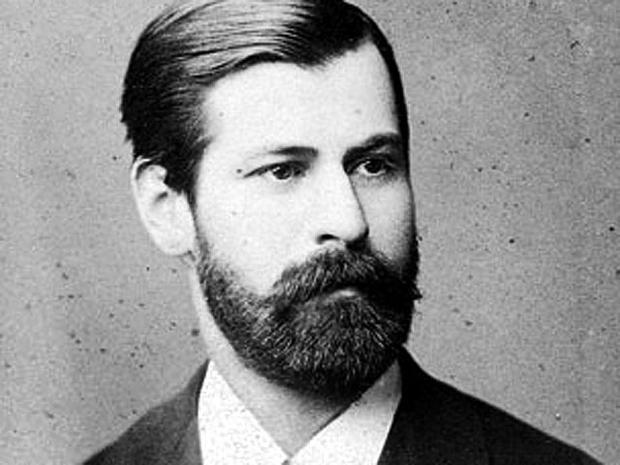

In 1865, the nine-year-old Freud entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. He proved an outstanding pupil and graduated from the Matura in 1873 with honors.

He loved literature and was proficient in German, French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin and Greek.

Freud entered the University of Vienna at age 17.

Photo: Freud (aged 16) and his mother, Amalia, in 1872.

Freud entered the University of Vienna at age 17.

Photo: Freud (aged 16) and his mother, Amalia, in 1872.

He joined the medical faculty at the university, where his studies included philosophy under Franz Brentano, physiology under Ernst Brücke, and zoology under Darwinist professor Carl Claus.

In 1876, Freud spent four weeks at Claus's zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels in an inconclusive search for their male reproductive organs.

In 1877 Freud moved to Ernst Brücke's physiology laboratory where he spent six years comparing the brains of humans and other vertebrates with those of invertebrates such as frogs, crayfish and lampreys.

His research work on the biology of nervous tissue proved seminal for the subsequent discovery of the neuron in the 1890s.

Freud's research work was interrupted in 1879 by the obligation to undertake a year's compulsory military service.

Freud's research work was interrupted in 1879 by the obligation to undertake a year's compulsory military service.

The lengthy downtimes enabled him to complete a commission to translate four essays from John Stuart Mill's collected works.

He graduated with an MD in March 1881.

He graduated with an MD in March 1881.

In 1882, Freud began his medical career at the Vienna General Hospital.

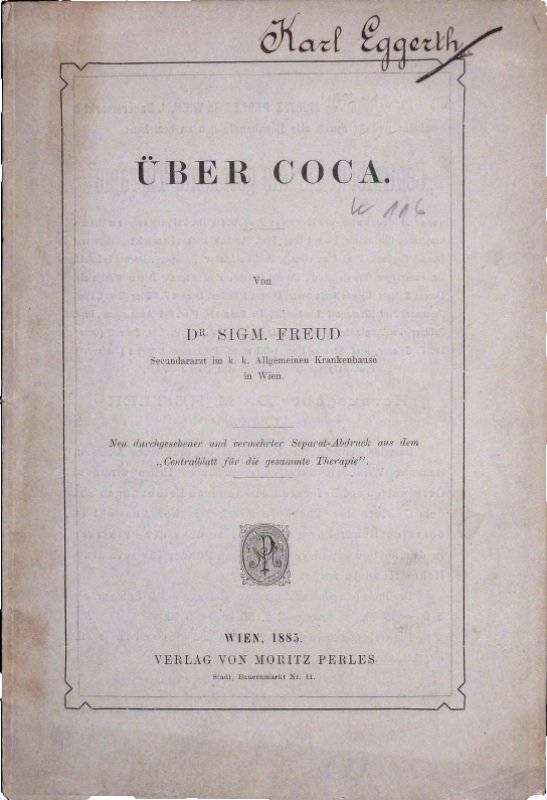

His research work in cerebral anatomy led to the publication of an influential paper on the palliative effects of cocaine in 1884.

As a medical researcher, Freud was an early user and proponent of cocaine as a stimulant as well as analgesic. He believed that cocaine was a cure for many mental and physical problems, and in his 1884 paper "On Coca" he extolled its virtues.

Between 1883 and 1887 he wrote several articles recommending medical applications, including its use as an antidepressant. He narrowly missed out on obtaining scientific priority for discovering its anesthetic properties of which he was aware but had mentioned only in passing.

(Karl Koller, a colleague of Freud's in Vienna, received that distinction in 1884 after reporting to a medical society the ways cocaine could be used in delicate eye surgery.)

Freud also recommended cocaine as a cure for morphine addiction.

Freud also recommended cocaine as a cure for morphine addiction.

He had introduced cocaine to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow who had become addicted to morphine taken to relieve years of excruciating nerve pain resulting from an infection acquired while performing an autopsy.

His claim that Fleischl-Marxow was cured of his addiction was premature, though he never acknowledged he had been at fault.

Fleischl-Marxow developed an acute case of "cocaine psychosis", and soon returned to using morphine, dying a few years later after more suffering from intolerable pain.

The application as an anesthetic turned out to be one of the few safe uses of cocaine, and as reports of addiction and overdose began to filter in from many places in the world, Freud's medical reputation became somewhat tarnished.

After the "Cocaine Episode" Freud ceased to publicly recommend use of the drug, but continued to take it himself occasionally for depression, migraine and nasal inflammation during the early 1890s, before discontinuing in 1896.

In 1886, Freud resigned his hospital post and entered private practice specializing in "nervous disorders". The same year he married Martha Bernays, the granddaughter of Isaac Bernays, a chief rabbi in Hamburg. The couple had six children.

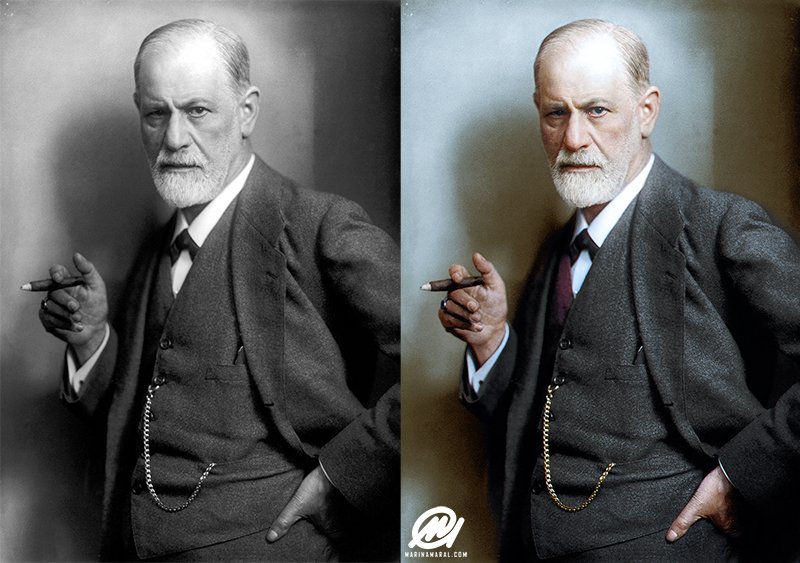

Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24. Initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker. He believed that smoking enhanced his capacity to work and that he could exercise self-control in moderating it.

Despite health warnings from colleague Wilhelm Fliess, he remained a smoker, eventually suffering a buccal cancer.

Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, "the one great habit."

Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, "the one great habit."

Freud had greatly admired his philosophy tutor, Brentano, who was known for his theories of perception and introspection. Brentano discussed the possible existence of the unconscious mind in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874).

Although Brentano denied its existence, his discussion of the unconscious probably helped introduce Freud to the concept. He owned and made use of Charles Darwin's major evolutionary writings, and was also influenced by Eduard von Hartmann's The Philosophy of the Unconscious.

Though Freud was reluctant to associate his psychoanalytic insights with prior philosophical theories, attention has been drawn to analogies between his work and that of both Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, both of whom he claimed not to have read until late in life.

One historian concluded, based on Freud's correspondence with his adolescent friend Eduard Silberstein, that Freud read Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy and the first two of the Untimely Meditations when he was 17.

In 1900, the year of Nietzsche's death, Freud bought his collected works; he told his friend, Fliess, that he hoped to find in Nietzsche's works "the words for much that remains mute in me." Later, he said he had not yet opened them.

Freud read William Shakespeare in English throughout his life, and it has been suggested that his understanding of human psychology may have been partially derived from Shakespeare's plays.

In October 1885, he went to Paris on a fellowship to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who was conducting scientific research into hypnosis.

He was later to recall the experience of this stay as catalytic in turning him toward the practice of medical psychopathology and away from a less financially promising career in neurology research.

Charcot specialized in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis, which he frequently demonstrated with patients on stage in front of an audience. Once he had set up in private practice in 1886, Freud began using hypnosis in his clinical work.

André Brouillet's, 1887: A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière depicting a Charcot demonstration. Freud had a lithograph of this painting placed over the couch in his consulting rooms.

The uneven results of Freud's early clinical work eventually led him to abandon hypnosis, having reached the conclusion that more consistent and effective symptom relief could be achieved by encouraging patients to talk freely, without censorship or inhibition

about whatever ideas or memories occurred to them. In conjunction with this procedure, which he called "free association", Freud found that patients' dreams could be fruitfully analyzed to reveal the complex structuring of unconscious material and to demonstrate the psychic

action of repression which, he had concluded, underlay symptom formation. By 1896 he was using the term "psychoanalysis" to refer to his new clinical method and the theories on which it was based.

Freud's development of these new theories took place during a period in which he experienced heart irregularities, disturbing dreams and periods of depression, a "neurasthenia" which he linked to the death of his father in 1896

and which prompted a "self-analysis" of his own dreams and memories of childhood. His explorations of his feelings of hostility to his father and rivalrous jealousy over his mother's affections led him to fundamentally revise his theory of the origin of the neuroses.

On the basis of his early clinical work, Freud had postulated that unconscious memories of sexual molestation in early childhood were a necessary precondition for the psychoneuroses (hysteria and obsessional neurosis), a formulation now known as Freud's seduction theory.

In the light of his self-analysis, Freud abandoned the theory that every neurosis can be traced back to the effects of infantile sexual abuse, now arguing that infantile sexual scenarios still had a causative function, but it did not matter whether they were real or imagined and

that in either case they became pathogenic only when acting as repressed memories.

This transition from the theory of infantile sexual trauma as a general explanation of how all neuroses originate to one that presupposes an autonomous infantile sexuality provided the basis for Freud's subsequent formulation of the theory of the Oedipus complex.

In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, published in 1905, Freud elaborates his theory of infantile sexuality, describing its "polymorphously perverse" forms and the functioning of the "drives", to which it gives rise, in the formation of sexual identity.

The same year he published ‘Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria (Dora)' which became one of his more famous and controversial case studies.

Freud's case study was condemned in its first review as a form of mental masturbation, an immoral misuse of his medical position.

During this formative period of his work, Freud valued and came to rely on the intellectual and emotional support of his friend Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin based ear, nose and throat specialist whom he had first met 1887.

Both men saw themselves as isolated from the prevailing clinical and theoretical mainstream because of their ambitions to develop radical new theories of sexuality.

Fliess developed highly eccentric theories of human biorhythms and a nasogenital connection which are today considered pseudoscientific.

He shared Freud's views on the importance of certain aspects of sexuality — masturbation, coitus interruptus, and the use of condoms — in the etiology of what was then called the "actual neuroses," primarily neurasthenia and certain physically manifested anxiety symptoms.

They maintained an extensive correspondence from which Freud drew on Fliess's speculations on infantile sexuality and bisexuality to elaborate and revise his own ideas.

His first attempt at a systematic theory of the mind, his Project for a Scientific Psychology was developed as a metapsychology with Fliess as interlocutor.

Freud had Fliess repeatedly operate on his nose and sinuses to treat "nasal reflex neurosis", and subsequently referred his patient Emma Eckstein to him.

According to Freud, her history of symptoms included severe leg pains with consequent restricted mobility, and stomach and menstrual pains. These pains were, according to Fliess's theories, caused by habitual masturbation which, as the tissue of the nose and genitalia were linked

was curable by removal of part of the middle turbinate.

Fliess's surgery proved disastrous, resulting in profuse, recurrent nasal bleeding - he had left a half-meter of gauze in Eckstein's nasal cavity the subsequent removal of which left her permanently disfigured.

Fliess's surgery proved disastrous, resulting in profuse, recurrent nasal bleeding - he had left a half-meter of gauze in Eckstein's nasal cavity the subsequent removal of which left her permanently disfigured.

Freud later concluded that a combination of a homoerotic attachment and the residue of his "specifically Jewish mysticism" lay behind his loyalty to his Jewish friend and his consequent over-estimation of both his theoretical and clinical work.

Their friendship came to an acrimonious end with Fliess angry at Freud's unwillingness to endorse his general theory of sexual periodicity and accusing him of collusion in the plagiarism of his work.

In January 1933, the Nazi Party took control of Germany, and Freud's books were prominent among those they burned and destroyed. Freud remarked: "What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books."

Freud continued to underestimate the growing Nazi threat and remained determined to stay in Vienna, even following the Anschluss of 13 March 1938, in which Nazi Germany annexed Austria, and the outbreaks of violent anti-Semitism that ensued.

Ernest Jones, the then president of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA), flew into Vienna from London via Prague on 15 March determined to get Freud to change his mind and seek exile in Britain.

This prospect and the shock of the arrest and interrogation of Anna Freud by the Gestapo finally convinced Freud it was time to leave Austria.

The departure from Vienna began in stages throughout April and May 1938.

The departure from Vienna began in stages throughout April and May 1938.

Freud's grandson Ernst Halberstadt and Freud's son Martin's wife and children left for Paris in April. Freud's sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, left for London on 5 May, Martin Freud the following week and Freud's daughter Mathilde and her husband, Robert Hollitscher, on 24 May.

Freud, his wife Martha and daughter Anna left Vienna on 4 June, accompanied by their housekeeper and a doctor, arriving in Paris the following day where they stayed as guests of Princess Bonaparte before travelling overnight to London arriving at Victoria Station on 6 June.

By mid-September 1939, Freud's cancer of the jaw was causing him increasingly severe pain and had been declared to be inoperable.

He died around midnight on 23 September 1939.

He died around midnight on 23 September 1939.

Freud's last home, now dedicated to his life and work as the Freud Museum, 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, London NW3, England.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh